Week 4: Rights, Policies, and Fairness in AI

DSAN 5450: Data Ethics and Policy

Spring 2026, Georgetown University

Fair Machine Learning? In This Economy?

- A cool algorithm ✅ (other DSAN classes)

- [Possibly benign, possibly biased] Training data ✅ (HW1)

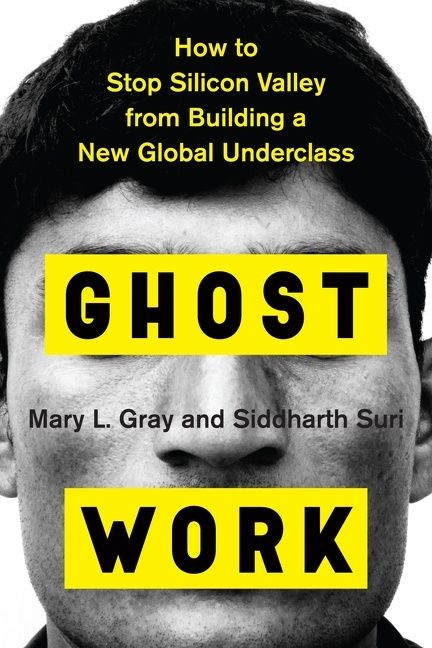

- \(\Longrightarrow\) Exploitation of below-minimum-wage human labor 😞🤐 (Dube et al. 2020, like and subscribe yall ❤️)

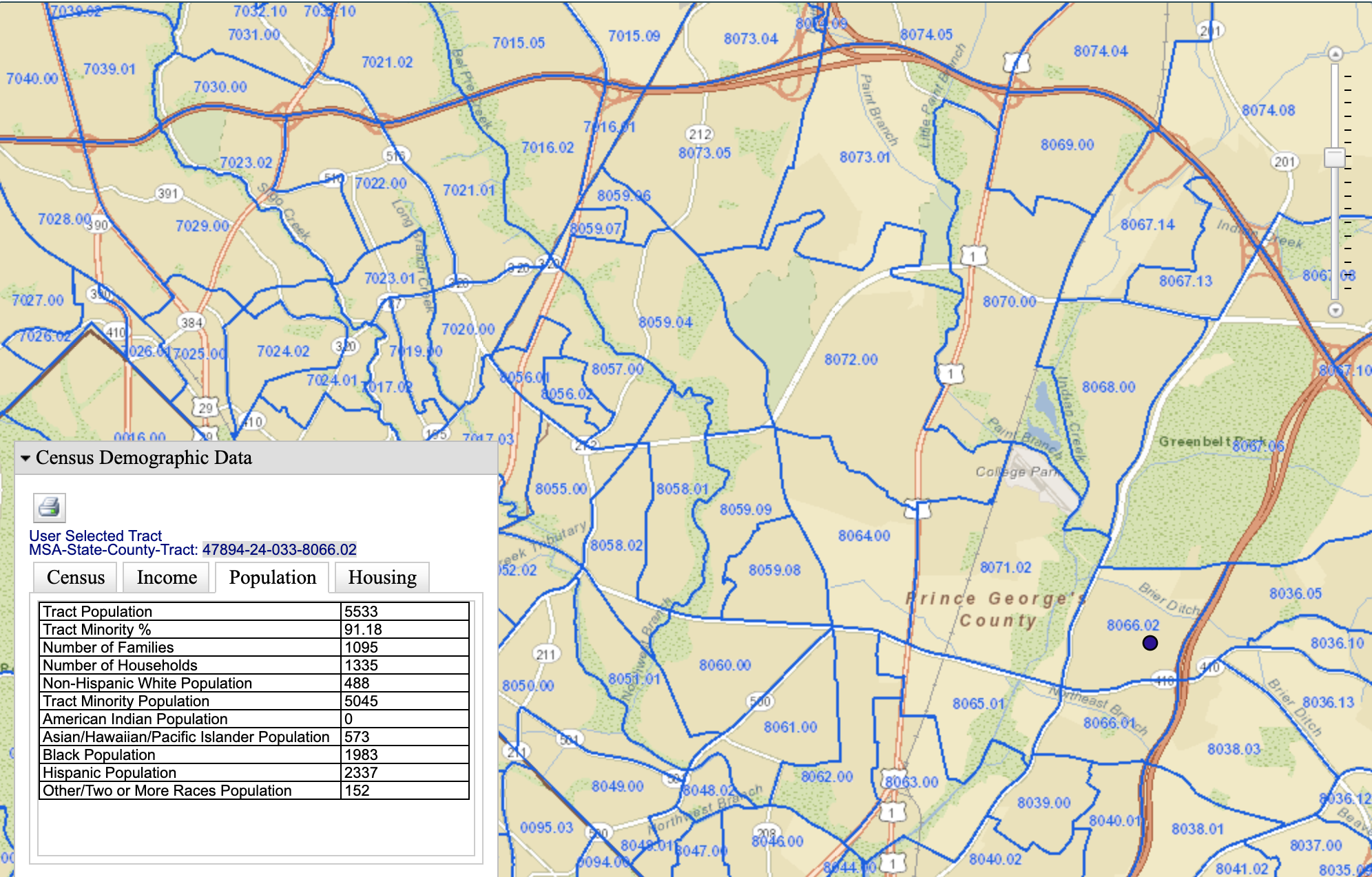

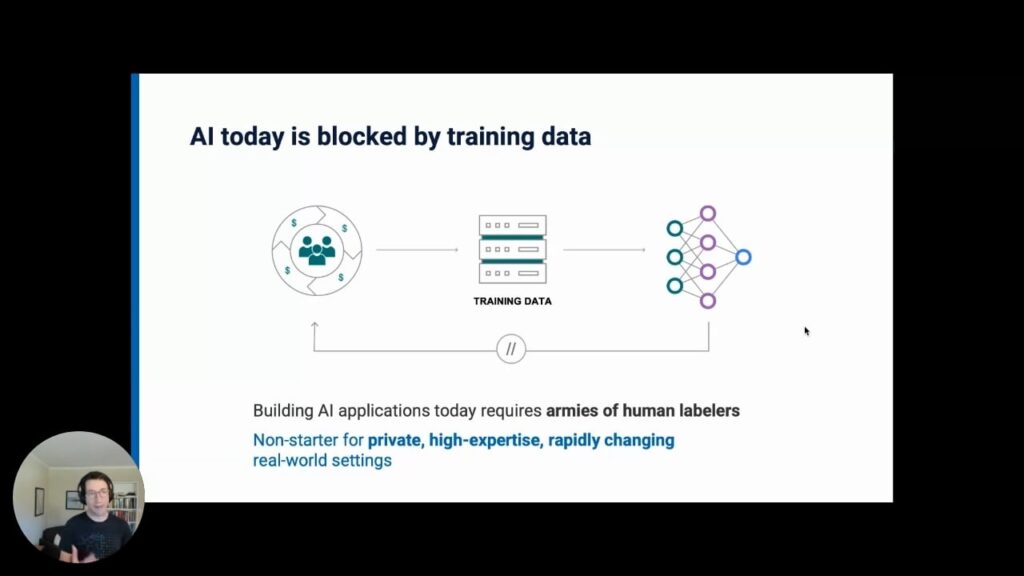

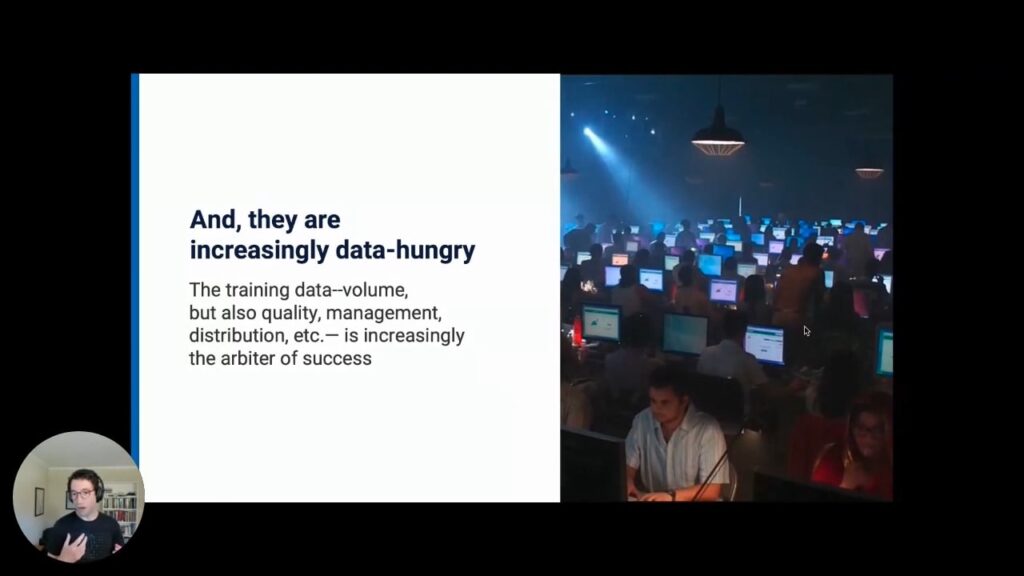

Part 3: The “Training Data Bottleneck”

With so much technical progress […] why is there so little real enterprise success? The answer all too often is that many enterprises continue to be bottlenecked by one key ingredient: the large amounts of labeled data [needed] to train these new systems.

Human Labor

Computer Scientists Being Responsible at Georgetown!

- (PS… UMD CS class of 2013 extremely overrepresented here 😜 go Terps

)

)

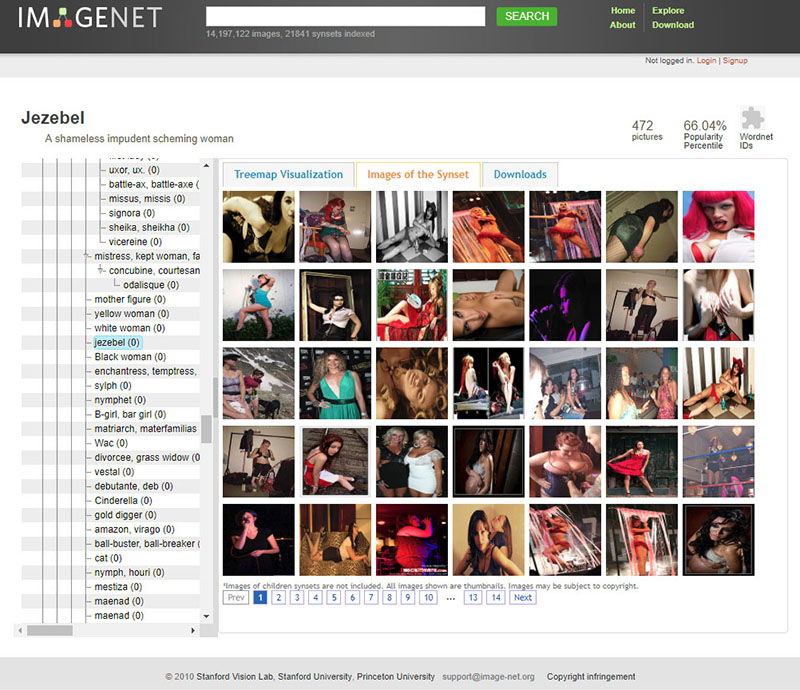

What Comes With Human Labels? Human Biases!

AI Machine Go Brrr

Biases In Our Brains → Biases in Our Models → Material Effects

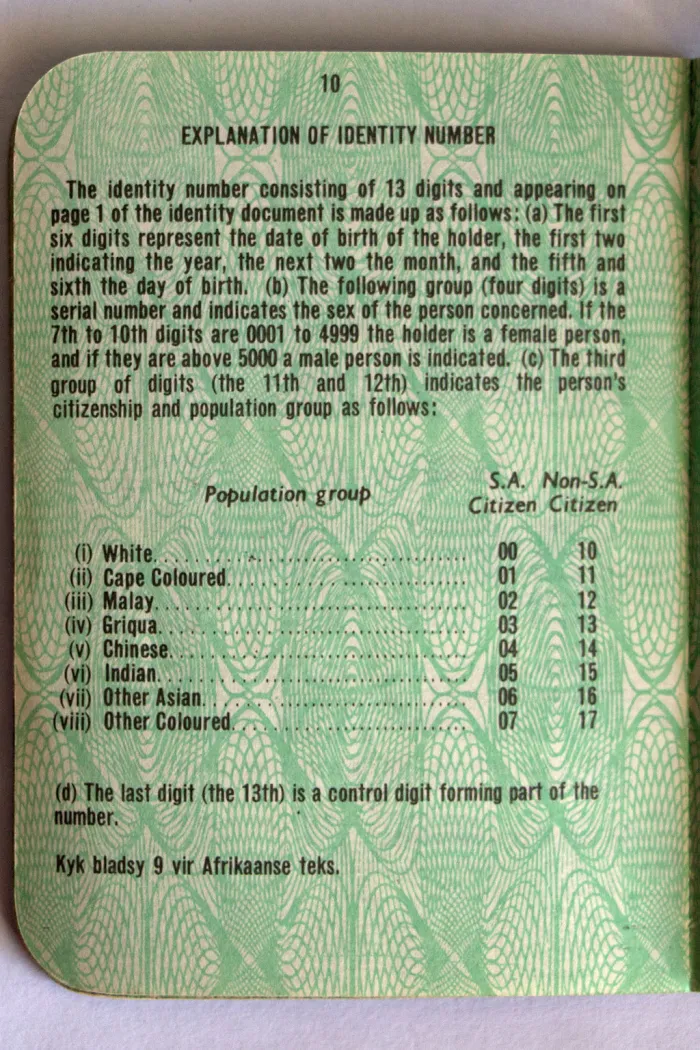

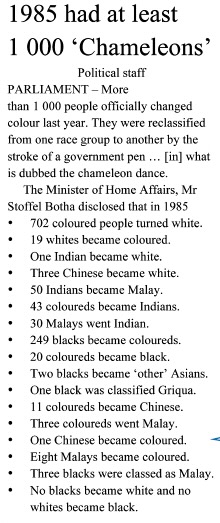

- “Reification”: Pretentious word for an important phenomenon, whereby talking about something (e.g., race) as if it was real ends up leading to it becoming real (having real impacts on people’s lives)1

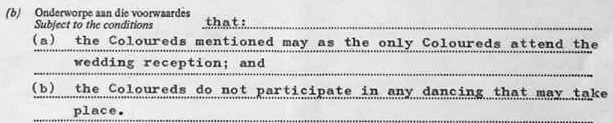

On average, being classified as White as opposed to Coloured would have more than quadrupled a person’s income. (Pellicer and Ranchhod 2023)

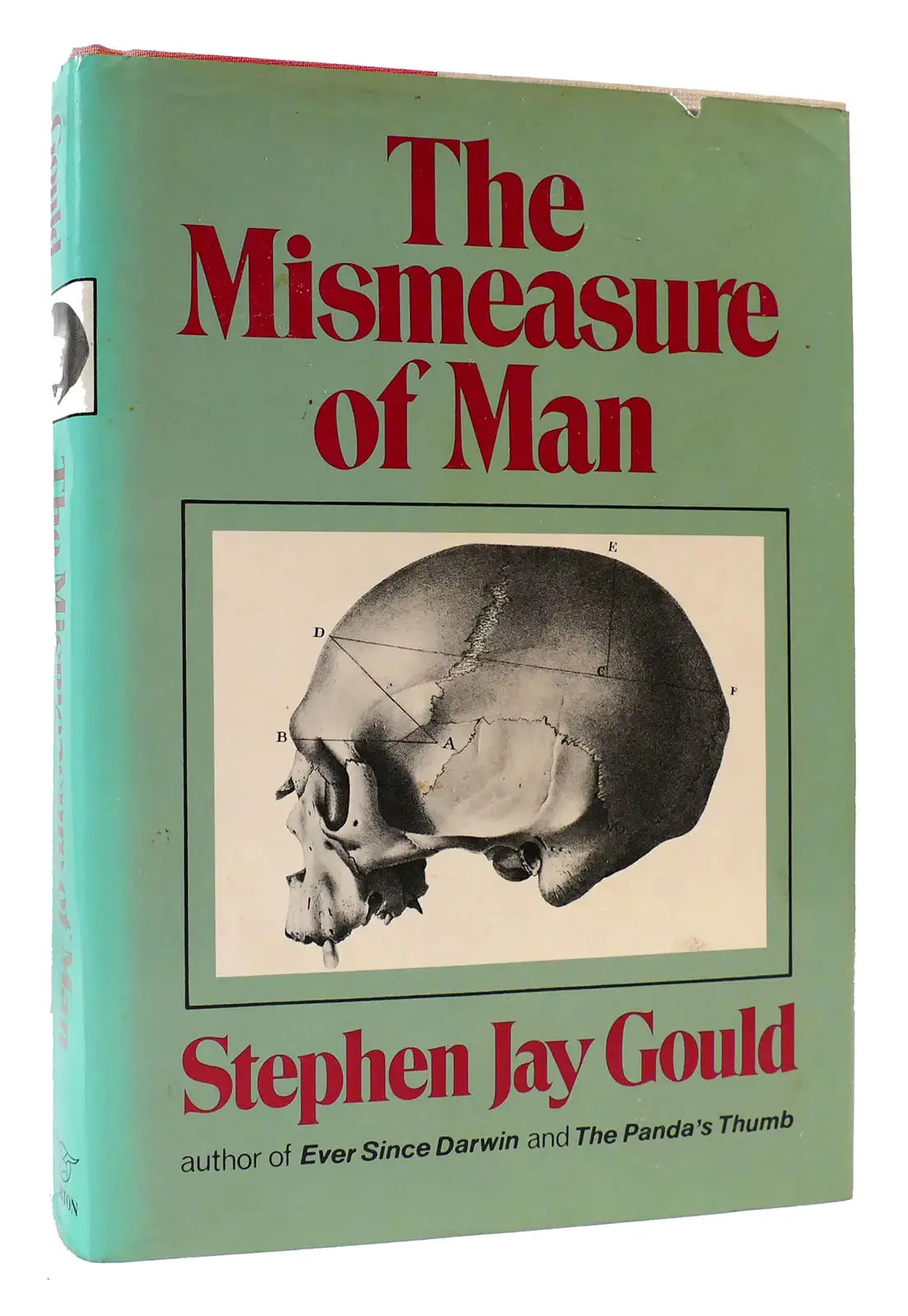

Reification in Science

- Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”

- Cat-and-mouse game between goals (🚩) and ways of measuring progress towards goals (also 🚩)

Metaethics

A scary-sounding word that just means:

“What we talk about when we talk about ethics”,

in contrast to

“What we talk about when we talk about [insert particular ethical framework here]”

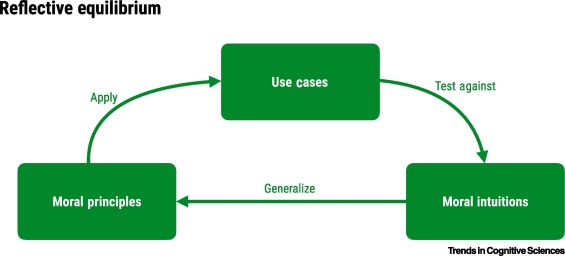

Reflective Equilibrium

- Most criticisms of any framework boil down to, “great in theory, but doesn’t work in practice”

- The way to take this seriously: reflective equilibrium

- Introduced by Rawls (1951), but popularized by Rawls (1971)

Normative vs. Descriptive Quick Recap

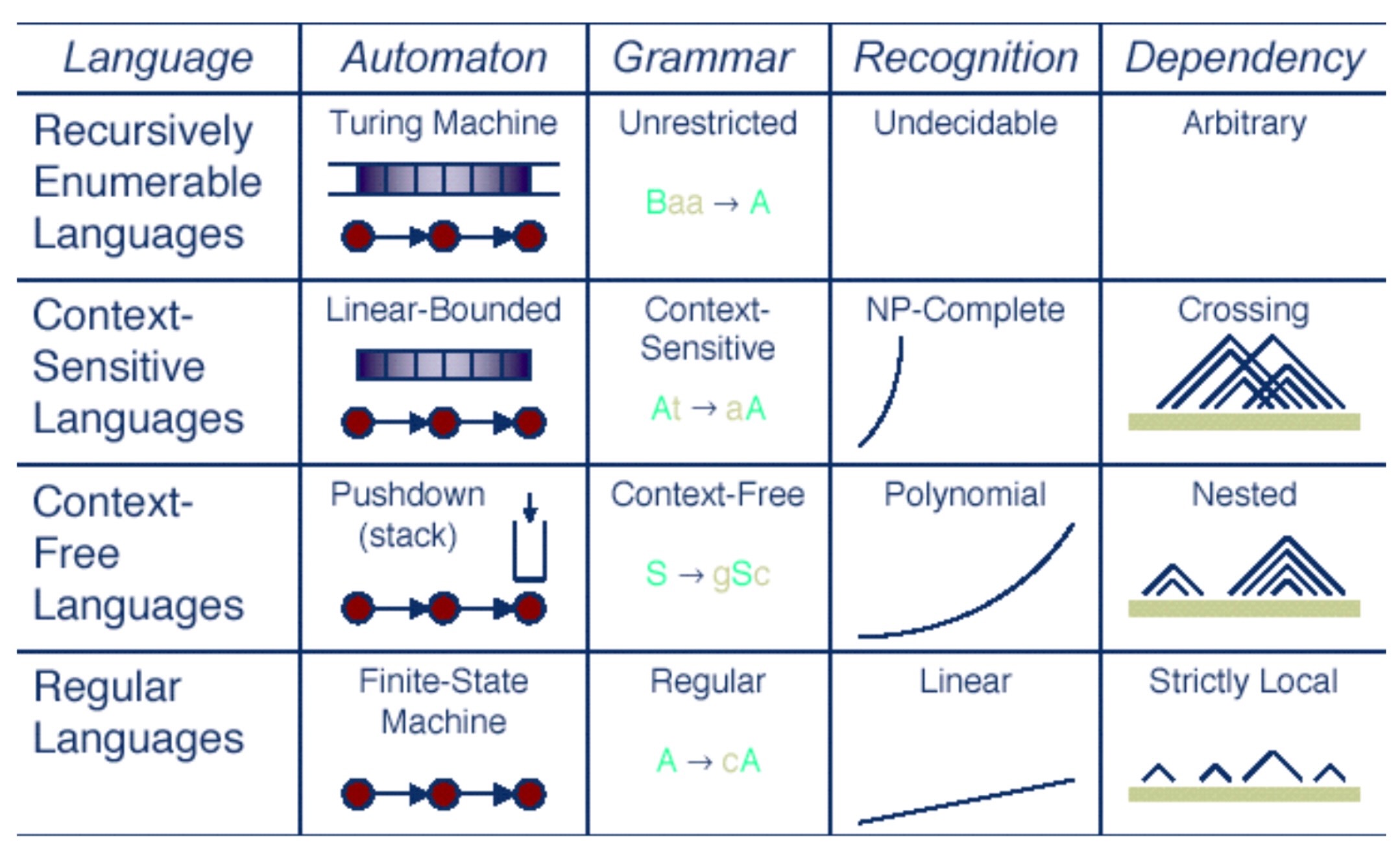

- Languages are arbitrary conventions for communication

- Ethical systems build on this language to non-arbitrarily mark out things that are good/bad

- Society wouldn’t be too different if we “shuffled” words (we’d just vibrate our vocal chords differently), but would be very different if we “shuffled” good/bad labeling

Changing Normative Values: Capitalism \(\leftrightarrow\) “Protestant Ethic”

- Big changes in history are associated with changes in this good/bad labeling!

- Max Weber (second most cited sociologist ever*): Protestant value system enabled capitalist system by relabeling what things are good vs. bad (Weber 1904):

Jesus said to his disciples, “Truly, I say to you, only with difficulty will a rich person enter the kingdom of heaven. Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.” (Matthew 19:23-24)

Oh, were we loving God worthily, we should have no love at all for money! (St. Augustine 1874, pg. 28)

*(…but remember: REIFICATION!)

The earliest capitalists lacked legitimacy in the moral climate in which they found themselves. One of the means they found [to legitimize their behavior] was to appropriate the evaluative vocabulary of Protestantism. (Skinner 2012, pg. 157)

Calvinism added [to Luther’s doctrine] the necessity of proving one’s faith in worldly activity, [replacing] spiritual aristocracy of monks outside of/above the world with spiritual aristocracy of predestined saints within it. (pg. 121).

Contemporary Example: Palestine

- Very few of the relevant empirical facts are in dispute, since opening of crucial archives to three so-called “New Historians” in the 1980s. So why do people still argue?

- Ilan Pappe, one of these historians, concluded from this material that:

- The Israeli state was built upon a massive ethnic cleansing, and

- Is not morally justifiable (Pappe 2006)

The immunity Israel has received over the last fifty years encourages others, regimes and oppositions alike, to believe that human and civil rights are irrelevant in the Middle East. The dismantling of the mega-prison in Palestine will send a different, and more hopeful, message.

- Utilitarian “wrapped” around Kantian

- Benny Morris, another of these historians, concluded that:

- The Israeli state was built upon a massive ethnic cleansing, and

- Is morally justifiable (Morris 1987)

A Jewish state would not have come into being without the uprooting of 700,000 Palestinians. Therefore it was necessary to uproot them. There was no choice but to expel that population. It was necessary to cleanse the hinterland and cleanse the border areas and cleanse the main roads.

- Straightforwardly utilitarian!

Nuts and Bolts for Fairness

One Final Reminder

- Industry rule #4080: Cannot “prove” \(q(x) = \text{``Algorithm }x\text{ is fair''}\)! Only \(p(x) \implies q(y)\):

\[ \underbrace{p(x)}_{\substack{\text{Accept ethical} \\ \text{framework }x}} \implies \underbrace{q(y)}_{\substack{\text{Algorithms should} \\ \text{satisfy condition }y}} \]

- Before: possible ethical frameworks (values for \(x\))

- Now: possible fairness criteria (values for \(y\))

Categories of Fairness Criteria

Roughly, approaches to fairness/bias in AI can be categorized as follows:

- Single-Threshold Fairness

- Equal Prediction

- Equal Decision

- Fairness via Similarity Metric(s)

- Causal Definitions

- [Today] Context-Free Fairness: Easier to grasp from CS/data science perspective; rooted in “language” of Machine Learning (you already know much of it, given DSAN 5000!)

- But easy-to-grasp notion \(\neq\) “good” notion!

- Your job: push yourself to (a) consider what is getting left out of the context-free definitions, and (b) the loopholes that are thus introduced into them, whereby people/computers can discriminate while remaining “technically fair”

Laws: Often Perfectly “Technically Fair”

Ah, la majestueuse égalité des lois, qui interdit au riche comme au pauvre de coucher sous les ponts, de mendier dans les rues et de voler du pain!

(Ah, the majestic equality of the law, which prohibits rich and poor alike from sleeping under bridges, begging in the streets, and stealing loaves of bread!)

Anatole France, Le Lys Rouge (France 1894)

Tumbling into Fairness

\[ \newcommand{\nimplies}{\;\not\!\!\!\!\implies} \]

“Repetition is the mother of perfection” - Dwayne Michael “Lil Wayne” Carter, Jr.

So How Should We Make/Choose Conventions?

- Hobbes (1668): Only way out of “war of all against all” is to surrender all power to one sovereign (the Leviathan)

- Rousseau (1762): Social contract

- [Big big ~200 year gap here… can you think of why? Hint: French Revolution in 1789]

- Rawls (1971): Social contract behind the “veil of ignorance”

- If we didn’t know where we were going to end up in society, how would we set it up?

Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance

- Probably the most important tool for policy whitepapers!

- “Justice as fairness” (next week: fairness in AI 😜)

- We don’t know whether we’ll be \(A\) or \(B\) in the intersection game, so we’d choose the traffic light!

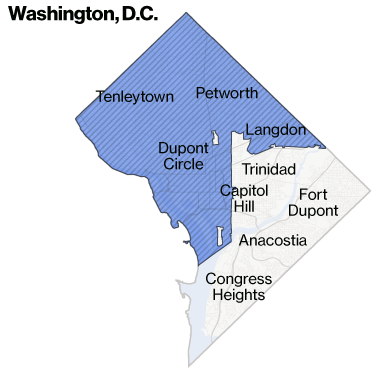

- More profoundly: We don’t know what race, gender, class, ethnicity, sexuality, disability status we’ll have; We don’t know whether we’ll be Israeli or Palestinian; we don’t know whether we’ll own means of production or own only our labor power (and thus have to sell it on a market to survive)… 🤔

Nuts and Bolts for Fairness

One Final Reminder

- Industry rule #4080: Cannot “prove” \(q(x) = \text{``Algorithm }x\text{ is fair''}\)! Only \(p(x) \implies q(y)\):

\[ \underbrace{p(x)}_{\substack{\text{Accept ethical} \\ \text{framework }x}} \implies \underbrace{q(y)}_{\substack{\text{Algorithms should} \\ \text{satisfy condition }y}} \]

- Before: possible ethical frameworks (values for \(x\))

- Now: possible fairness criteria (values for \(y\))

Categories of Fairness Criteria

Roughly, approaches to fairness/bias in AI can be categorized as follows:

- Single-Threshold Fairness

- Equal Prediction

- Equal Decision

- Fairness via Similarity Metric(s)

- Causal Definitions

- [Today] Context-Free Fairness: Easier to grasp from CS/data science perspective; rooted in “language” of Machine Learning (you already know much of it, given DSAN 5000!)

- But easy-to-grasp notion \(\neq\) “good” notion!

- Your job: push yourself to (a) consider what is getting left out of the context-free definitions, and (b) the loopholes that are thus introduced into them, whereby people/computers can discriminate while remaining “technically fair”

Laws: Often Perfectly “Technically Fair”

Ah, la majestueuse égalité des lois, qui interdit au riche comme au pauvre de coucher sous les ponts, de mendier dans les rues et de voler du pain!

(Ah, the majestic equality of the law, which prohibits rich and poor alike from sleeping under bridges, begging in the streets, and stealing loaves of bread!)

Anatole France, Le Lys Rouge (France 1894)

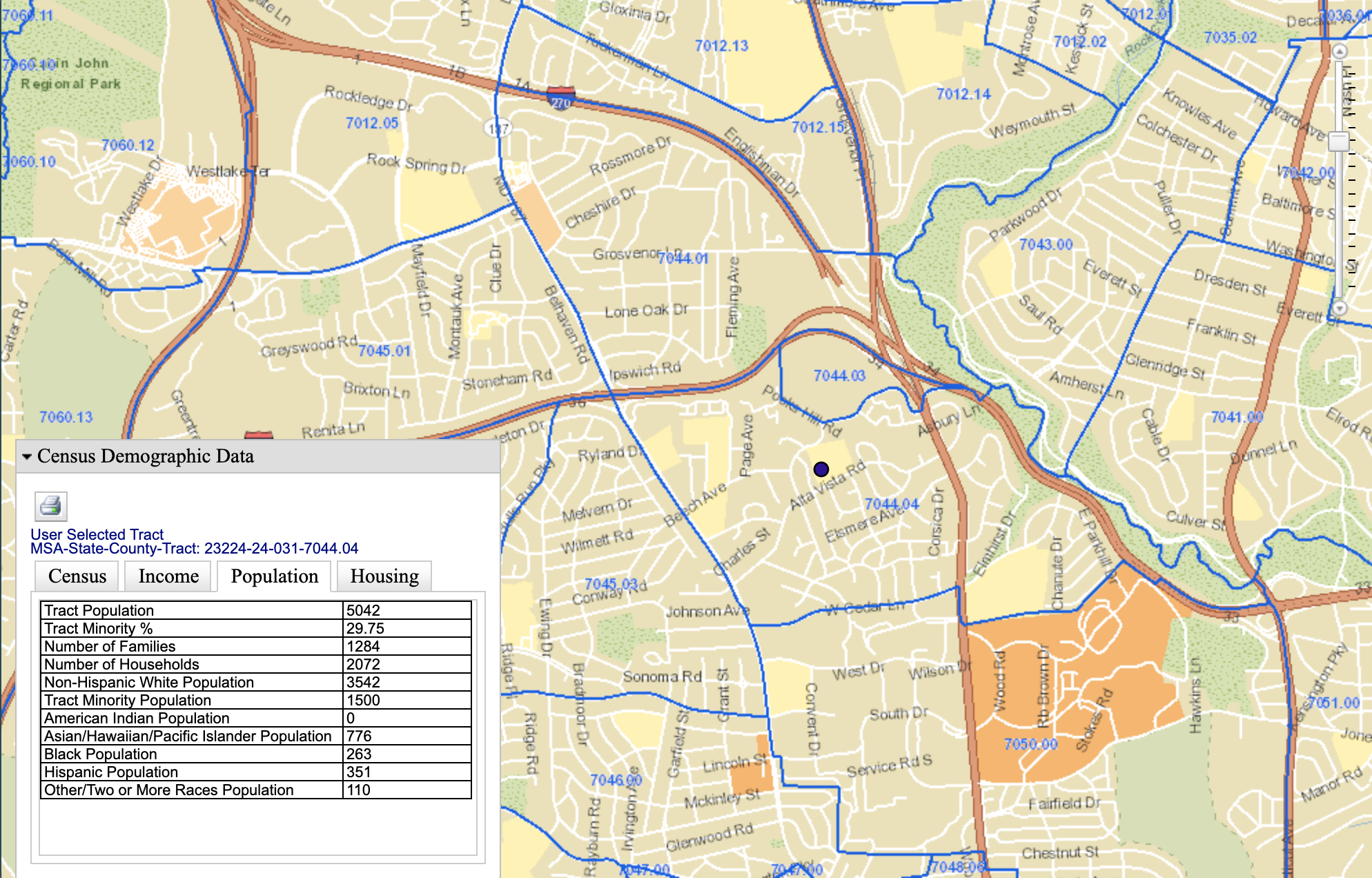

Definitions and (Impossibility) Results

(tldr:)

- We have information \(X_i\) about person \(i\), and

- We’re trying to predict a binary outcome \(Y_i\) involving \(i\).

- So, we use ML to learn a risk function \(r: \mathcal{R}_{X_i} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), then

- Use this to make a binary decision \(\widehat{Y}_i = \mathbf{1}[r(X_i) > t]\)

Protected/Sensitive Attributes

- Standard across the literature: Random Variable \(A_i\) “encoding” membership in protected/sensitive group. In HW1, for example:

\[ A_i = \begin{cases} 0 &\text{if }i\text{ self-reported ``white''} \\ 1 &\text{if }i\text{ self-reported ``black''} \end{cases} \]

Notice: choice of mapping into \(\{0, 1\}\) here non-arbitrary!

We want our models/criteria to be descriptively but also normatively robust; e.g.:

If (antecedent I hold, though majority in US do not) one believes that ending (much less repairing) centuries of unrelenting white supremacist violence here might require asymmetric race-based policies,

Then our model should allow different normative labels and differential weights on

\[ \begin{align*} \Delta &= (\text{Fairness} \mid A = 1) - (\text{Fairness} \mid A = 0) \\ \nabla &= (\text{Fairness} \mid A = 0) - (\text{Fairness} \mid A = 1) \end{align*} \]

despite the descriptive fact that \(\Delta = -\nabla\).

Where Descriptive and Normative Become Intertwined

- Allowing this asymmetry is precisely what enables bring descriptive facts to bear on normative concerns!

- Mathematically we can always “flip” the mapping from racial labels into \(\{0, 1\}\)…

- But this (in a precise, mathematical sense: namely, isomorphism) implies that we’re treating racial categorization as the same type of phenomenon as driving on left or right side of road (see: prev slides on why we make the descriptive vs. normative distinction)

- (See also: Sweden’s Dagen H!)

Lab Time!

“Fairness” Through Equalized Positive Rates (EPR)

\[ \boxed{\Pr(D = 1 \mid A = 0) = \Pr(D = 1 \mid A = 1)} \]

- This works specifically for discrete, binary-valued categories

- For general attributes (whether discrete or continuous!), generalizes to:

\[ \boxed{D \perp A} \iff \Pr(D = d, A = a) = \Pr(D = d)\Pr(A = a) \]

Imagine you learn that a person received a scholarship (\(D = 1\)); [with equalized positive rates], this fact would give you no knowledge about the race (or sex, or class, as desired) \(A\) of the individual in question. (DeDeo 2016)

Achieving Equalized Positive Rates

The good news: if we want this, there is a closed-form solution: take your datapoints \(X_i\) and re-weigh each point to obtain \(\widetilde{X}_i = w_iX_i\), where

\[ w_i = \frac{\Pr(Y_i = 1)}{\Pr(Y_i = 1 \mid A_i = 1)} \]

and use derived dataset \(\widetilde{X}_i\) to learn \(r(X)\) (via ML algorithm)… Why does this work?

Let \(\mathcal{X}_{\text{fair}}\) be the set of all possible reweighted versions of \(X_i\) ensuring \(Y_i \perp A_i\). Then

\[ \widetilde{X}_i = \min_{X_i' \in \mathcal{X}_{\text{fair}}}\textsf{distance}(X_i', X_i) = \min_{X_i' \in \mathcal{X}_{\text{fair}}}\underbrace{KL(X_i' \| X_i)}_{\text{Relative entropy!}} \]

- The bad news: nobody in the fairness in AI community read DeDeo (2016), which proves this using information theory? Idk. It has a total of 22 citations 😐

“Fairness” Through Equalized Error Rates

Equalized positive rates didn’t take outcomes \(Y_i\) into account…

- (Even if \(A_i = 1 \Rightarrow Y_i = 1, A_i = 0 \Rightarrow Y_i = 0\), we’d have to choose \(\widehat{Y}_i = c\))

This time, we consider the outcome \(Y\) that

Equalized False Positive Rate (EFPR):

\[ \Pr(D = 1 \mid Y = 0, A = 0) = \Pr(D = 1 \mid Y = 0, A = 1) \]

- Equalized False Negative Rate (EFNR):

\[ \Pr(D = 0 \mid Y = 1, A = 0) = \Pr(D = 0 \mid Y = 1, A = 1) \]

- For general (non-binary) attributes: \((D \perp A) \mid Y\):

\[ \Pr(D = d, A = a \mid Y = y) = \Pr(D = d \mid Y = y)\Pr(A = a \mid Y = y) \]

⚠️ LESS EQUATIONS PLEASE! 😤

- Depending on your background and/or learning style (say, visual vs. auditory), you may be able to look at equations on previous two slides and “see” what they’re “saying”

- If your brain works similarly to mine, however, your eyes glazed over, you began dissociating, planning an escape route, etc., the moment \(> 2\) variables appeared

- If you’re in the latter group, welcome to the cult of Probabilistic Graphical Models 😈

- Our first measure that 🥳🎉matches a principle of justice in society!!!🕺🪩

- Blackstone’s Ratio: “It is better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffers.” (Blackstone 1769)

- (…break time!)

Back to Equalized Error Rates

- Blackstone’s Ratio: “It is better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffers.” (Blackstone 1769)

- Mathematically \(\Rightarrow \text{Cost}(FPR) = 10\cdot \text{Cost}(FNR)\)

- Legally \(\Rightarrow\) beyond reasonable doubt standard for conviction

- EFPR \(\iff\) rates of false conviction should be the same for everyone, including members of different racial groups.

- Violated when black people are disproportionately likely to be incorrectly convicted, as if a lower evidentiary standard were applied to black people.

One Final Context-Free Criterion: Calibration

- A risk function \(r(X)\) is calibrated if

\[ \Pr(Y = 1 \mid r(X) = v_r) = v_r \]

- (Sweeping a lot of details under the rug), I see this one as: the risk function “tracks” real-world probabilities

- Then, \(r(X)\) is calibrated by group if

\[ \Pr(Y = y \mid r(X) = v_r, A = a) = v_r \]

Impossibility Results

- tldr: We cannot possibly achieve all three of equalized positive rates (often also termed “anti-classification”), classification parity, and calibration (regardless of base rates)

- More alarmingly: We can’t even achieve both classification parity and calibration, except in the special case of equal base rates

“Impossibility” vs. Impossibility

- Sometimes “impossibility results” are, for all intents and purposes, mathematical curiosities: often there’s some pragmatic way of getting around them

- Example: “Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem”

- [In theory] It is mathematically impossible to aggregate individual preferences into societal preferences

- [The catch] True only if people are restricted to ordinal preferences: “I prefer \(x\) to \(y\).” No more information allowed

- [The way around it] Allow people to indicate the magnitude of their preferences: “I prefer \(x\) 5 times more than \(y\)”

- In this case, though, there are direct and (often) unavoidable real-world barriers that fairness impossibility imposes 😕

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

- Aziza, Bogdan, and Charles are competing in a fitness test with four events. Goal: determine who is most fit overall

| Run | Jump | Hurdle | Weights | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aziza | 10.1” | 6.0’ | 40” | 150 lb |

| Bogdan | 9.2” | 5.9’ | 42” | 140 lb |

| Charles | 10.0” | 6.1’ | 39” | 145 lb |

- We can rank unambiguously on individual events: Jump: Charles \(\succ_J\) Aziza \(\succ_J\) Bogdan

- Now, axioms for aggregation:

- \(\text{WP}\) (Weak Pareto Optimality): if \(x \succ_i y\) for all events \(i\), \(x \succ y\)

- \(\text{IIA}\) (Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives): If a fourth competitor enters, but Aziza and Bogdan still have the same relative standing on all events, their relative standing overall should not change

- Long story short: only aggregation that can satisfy these is “dictatorship”: choose one event, give it importance of 100%, the rest have importance 0% 😰

ProPublica vs. Northpointe

- This is… an example with 1000s of books and papers and discussions around it! (A red flag 🚩, since, obsession with one example may conceal much wider range of issues!)

- But, tldr, Northpointe created a ML algorithm called COMPAS, used by court systems all over the US to predict “risk” of arrestees

- In 2016, ProPublica published results from an investigative report documenting COMPAS’s racial discrimination, in the form of violating equal error rates between black and white arrestees

- Northpointe responded that COMPAS does not discriminate, as it satisfies calibration

- People have argued about who is “right” for 8 years, with some progress, but… not a lot

So… What Do We Do?

- One option: argue about which of the two definitions is “better” for the next 100 years (what is the best way to give food to the poor?)

It appears to reveal an unfortunate but inexorable fact about our world: we must choose between two intuitively appealing ways to understand fairness in ML. Many scholars have done just that, defending either ProPublica’s or Northpointe’s definitions against what they see as the misguided alternative. (Simons 2023)

- Another option: study and then work to ameliorate the social conditions which force us into this realm of mathematical impossibility (why do the poor have no food?)

The impossibility result is about much more than math. [It occurs because] the underlying outcome is distributed unevenly in society. This is a fact about society, not mathematics, and requires engaging with a complex, checkered history of systemic racism in the US. Predicting an outcome whose distribution is shaped by this history requires tradeoffs because the inequalities and injustices are encoded in data—in this case, because America has criminalized Blackness for as long as America has existed.

Why Not Both??

- On the one hand: yes, both! On the other hand: fallacy of the “middle ground”

- We’re back at descriptive vs. normative:

- Descriptively, given 100 values \(v_1, \ldots, v_{100}\), their mean may be a good way to summarize, if we have to choose a single number

- But, normatively, imagine that these are opinions that people hold about fairness.

- Now, if it’s the US South in 1860 and \(v_i\) represents person \(i\)’s approval of slavery, from a sample of 100 people, then approx. 97 of the \(v_i\)’s are “does not disapprove” (Rousey 2001) — in this case, normatively, is the mean \(0.97\) the “correct” answer?

- We have another case where, like the “grass is green” vs. “grass ought to be green” example, we cannot just “import” our logical/mathematical tools from the former to solve the latter! (However: this does not mean they are useless! This is the fallacy of the excluded middle, sort of the opposite of the fallacy of the middle ground)

- This is why we have ethical frameworks in the first place! Going back to Rawls: “97% of Americans think black people shouldn’t have rights” \(\nimplies\)“black people shouldn’t have rights”, since rights are a primary good

References

Appendix: Slightly Deeper Dive into Descriptive vs. Normative Judgements

| Descriptive (Is) | Normative (Ought) |

|---|---|

| Grass is green (true) | Grass ought to be green (?) |

| Grass is blue (false) | Grass ought to be blue (?) |

Easy Mode: Descriptive Judgements

How did you acquire the concept “red”?

- People pointed to stuff with certain properties and said “red” (or “rojo” or “红”), as pieces of an intersubjective communication system

- These descriptive labels enable coordination, like driving on left or right side of road!

- Nothing very profound or difficult in committing to this descriptive coordination: “for ease of communication, I’ll vibrate my vocal chords like this (or write these symbols) to indicate \(x\), and vibrate them like this (or write these other symbols) to indicate \(y\)”

- Linguistic choices, when it comes to description, are arbitrary*: Our mouths can make these sounds, and each language is a mapping: [combinations of sounds] \(\leftrightarrow\) [things]

- diːsˈæn ˈfɪfti fɔr ˈfɪfti US Accent / Icelandic Accent

*(Tiny text footnote: Except for, perhaps, a few fun but rare onomatopoetic cases)

What Makes Ethical Judgements “More Difficult”?

How did you acquire the concept “good”?

- People pointed to actions with certain properties and said “good” (and pointed at others and said “bad”), as part of instilling values in you

- “Grass is green” just links two descriptive referents together, while “Honesty is good” takes the descriptive concept “honesty” and links it with the normative concept “good”

- In doing this, parents/teachers/friends are doing way more than just linking sounds and things in the world (describing): they are also prescribing rules of moral conduct!

- Normative concepts go beyond “mere” communication: course of your life / future / [things that matter deeply to people] differ if you act on one set of norms vs. another

- \(\implies\) Ethics centrally involves non-arbitrarily-chosen commitments!