Week 2: Linear Regression

DSAN 5300: Statistical Learning

Spring 2026, Georgetown University

Monday, January 12, 2026

Schedule

Today’s Planned Schedule:

| Start | End | Topic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lecture | 6:30pm | 7:10pm | Simple Linear Regression → |

| 7:10pm | 7:30pm | Deriving the OLS Solution → | |

| 7:30pm | 8:00pm | Interpreting OLS Output → | |

| Break! | 8:00pm | 8:10pm | |

| 8:10pm | 8:30pm | Quiz Review → | |

| 8:30pm | 9:00pm | Quiz 2! |

Linear Regression

What happens to my dependent variable \(Y\) when my independent variable \(X\) increases by 1 unit?

Keep the goal in front of your mind:

The Goal of Regression

Find a line \(\widehat{y} = mx + b\) that best predicts \(Y\) for given values of \(X\)

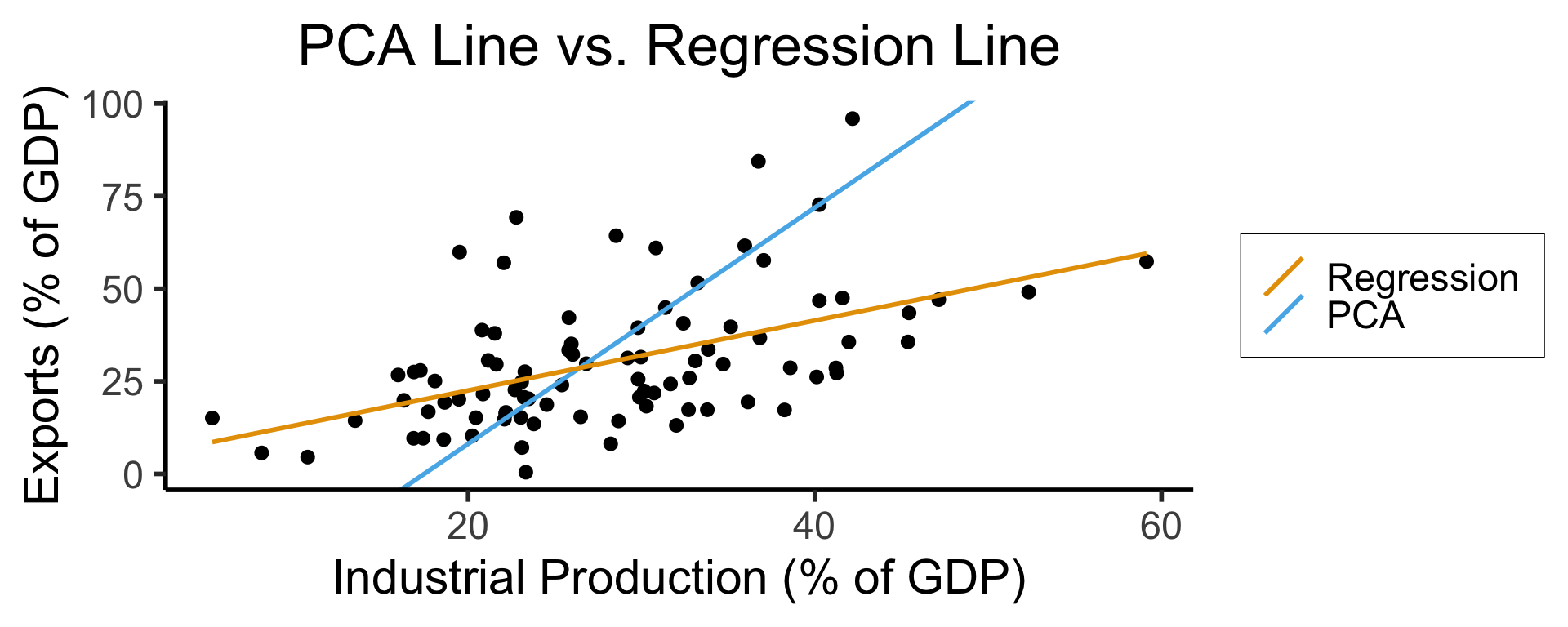

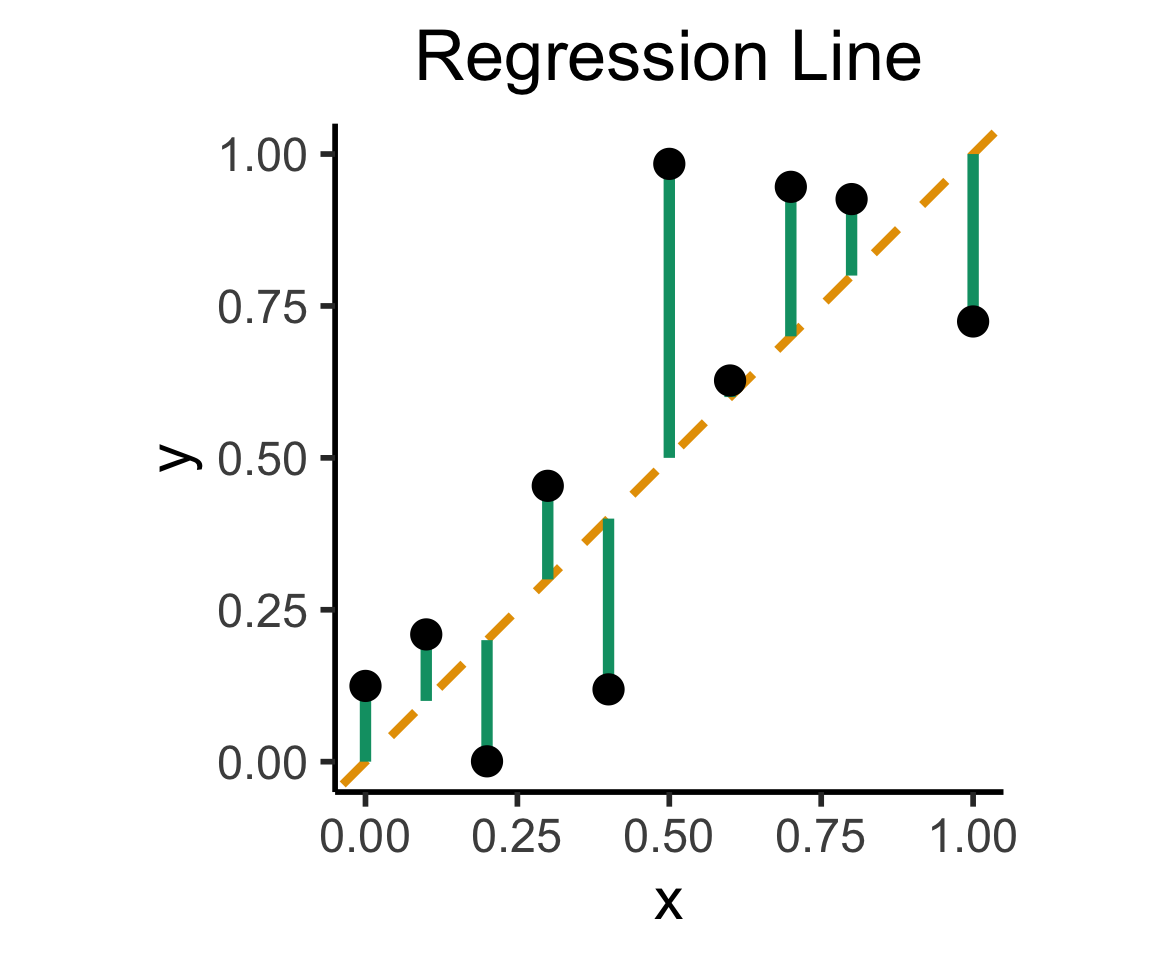

- Sanity Note 1: \(\Rightarrow\) measuring error via vertical distance from line

- Sanity Note 2: \(\Rightarrow\) modeling distribution of \(\boxed{Y \mid X}\), not \((X,Y)\)!

- Predicting \(Y\) from \(X\) and \(X\) from \(Y\) \(\Rightarrow\) principal component line \(\neq\) regression!

\[ \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmax}{argmax} \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmin}{argmin} \newcommand{\bigexp}[1]{\exp\mkern-4mu\left[ #1 \right]} \newcommand{\bigexpect}[1]{\mathbb{E}\mkern-4mu \left[ #1 \right]} \newcommand{\definedas}{\overset{\small\text{def}}{=}} \newcommand{\definedalign}{\overset{\phantom{\text{defn}}}{=}} \newcommand{\eqeventual}{\overset{\text{eventually}}{=}} \newcommand{\Err}{\text{Err}} \newcommand{\expect}[1]{\mathbb{E}[#1]} \newcommand{\expectsq}[1]{\mathbb{E}^2[#1]} \newcommand{\fw}[1]{\texttt{#1}} \newcommand{\given}{\mid} \newcommand{\green}[1]{\color{green}{#1}} \newcommand{\heads}{\outcome{heads}} \newcommand{\iid}{\overset{\text{\small{iid}}}{\sim}} \newcommand{\lik}{\mathcal{L}} \newcommand{\loglik}{\ell} \DeclareMathOperator*{\maximize}{maximize} \DeclareMathOperator*{\minimize}{minimize} \newcommand{\mle}{\textsf{ML}} \newcommand{\nimplies}{\;\not\!\!\!\!\implies} \newcommand{\orange}[1]{\color{orange}{#1}} \newcommand{\outcome}[1]{\textsf{#1}} \newcommand{\param}[1]{{\color{purple} #1}} \newcommand{\pgsamplespace}{\{\green{1},\green{2},\green{3},\purp{4},\purp{5},\purp{6}\}} \newcommand{\pedge}[2]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{~{#1}~} \rightarrow \; \enclose{circle}{\kern.01em {#2}~\kern.01em}} \newcommand{\pnode}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{\kern.1em {#1} \kern.1em}} \newcommand{\ponode}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{box}[background=lightgray]{{#1}}} \newcommand{\pnodesp}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{~{#1}~}} \newcommand{\purp}[1]{\color{purple}{#1}} \newcommand{\sign}{\text{Sign}} \newcommand{\spacecap}{\; \cap \;} \newcommand{\spacewedge}{\; \wedge \;} \newcommand{\tails}{\outcome{tails}} \newcommand{\Var}[1]{\text{Var}[#1]} \newcommand{\bigVar}[1]{\text{Var}\mkern-4mu \left[ #1 \right]} \]

How Do We Define “Best”?

- Intuitively, two different ways to measure how well a line fits the data:

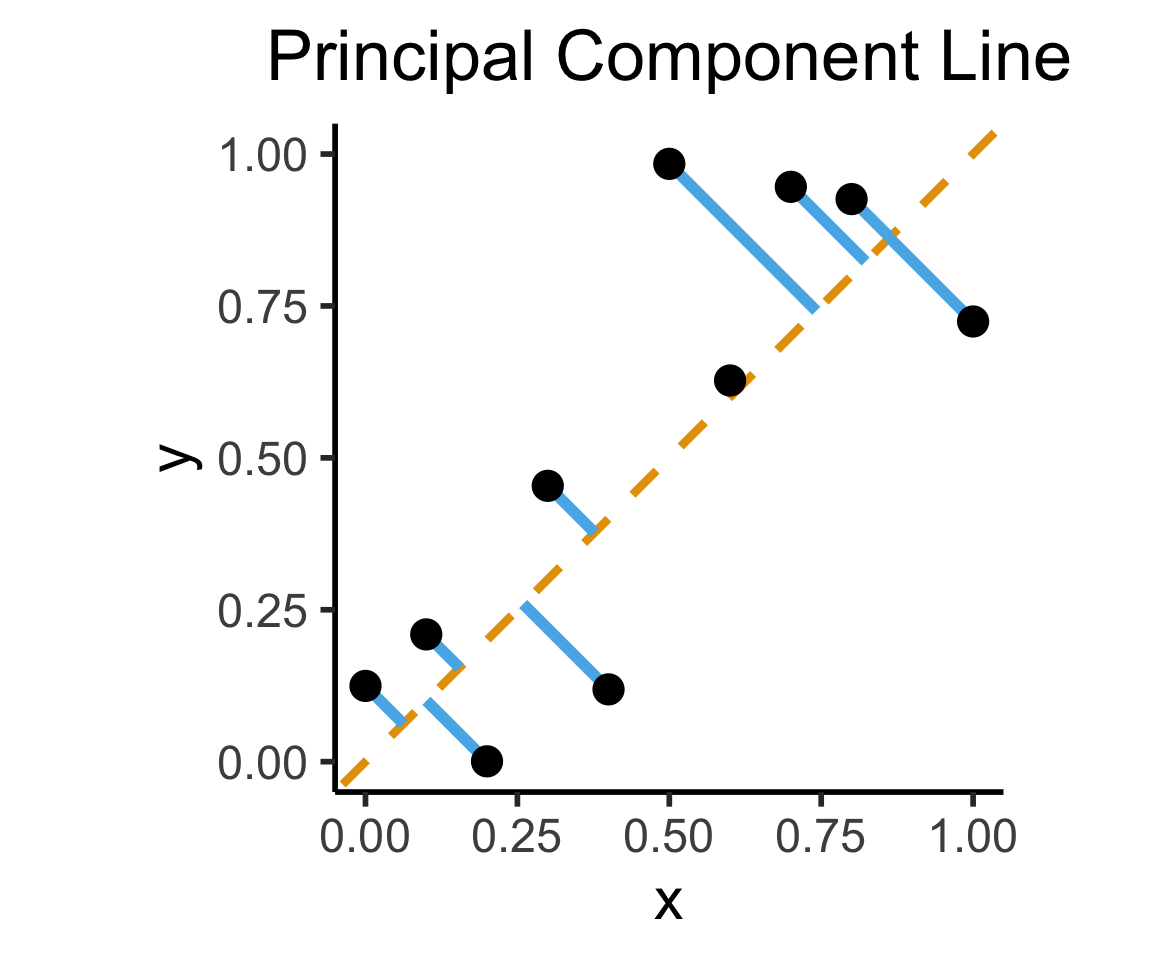

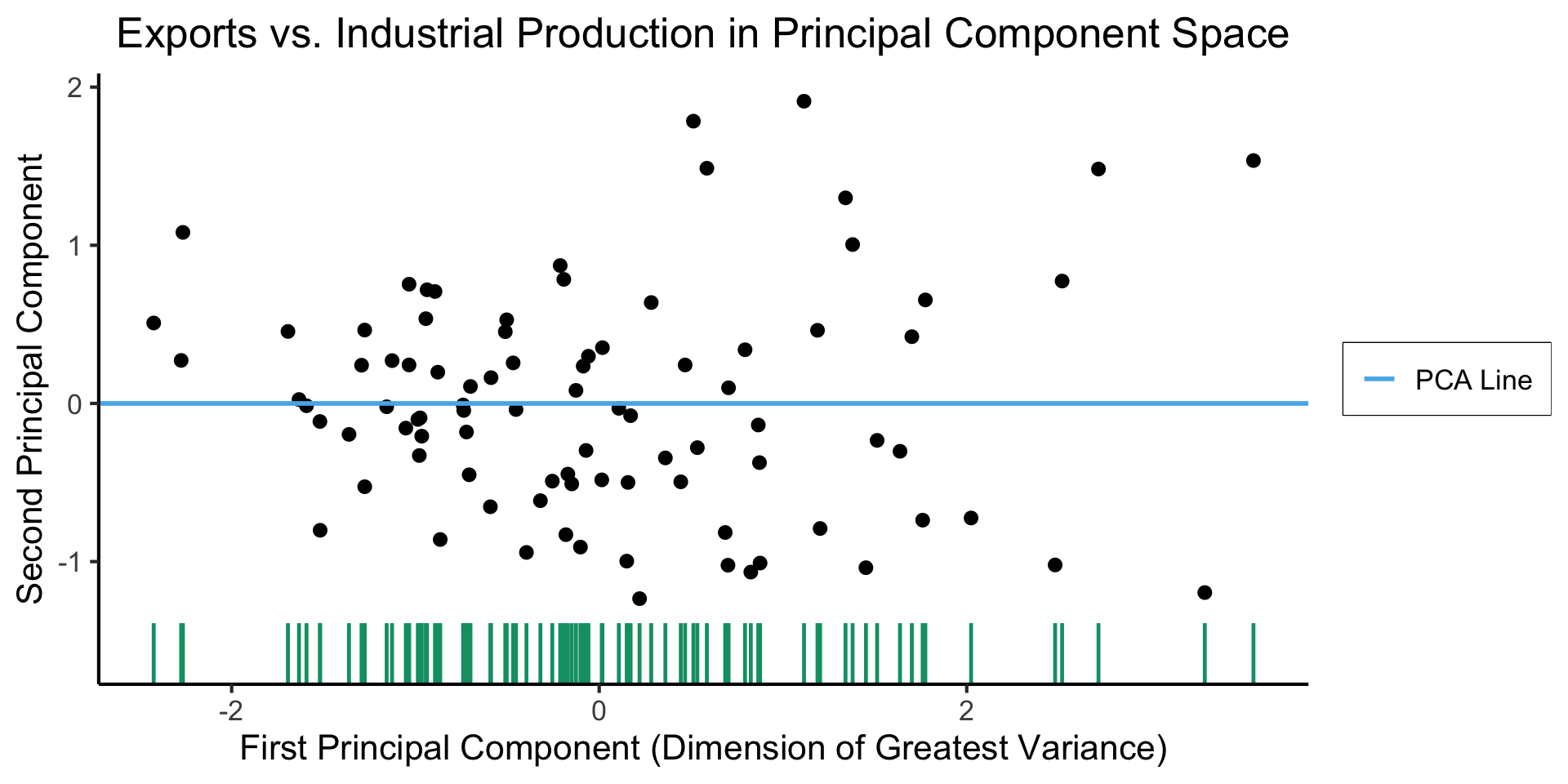

Principal Component Analysis

- Principal Component Line can be used to project the data onto its dimension of highest variance (recap from 5000!)

- More simply: PCA can discover meaningful axes in data (unsupervised learning / exploratory data analysis settings)

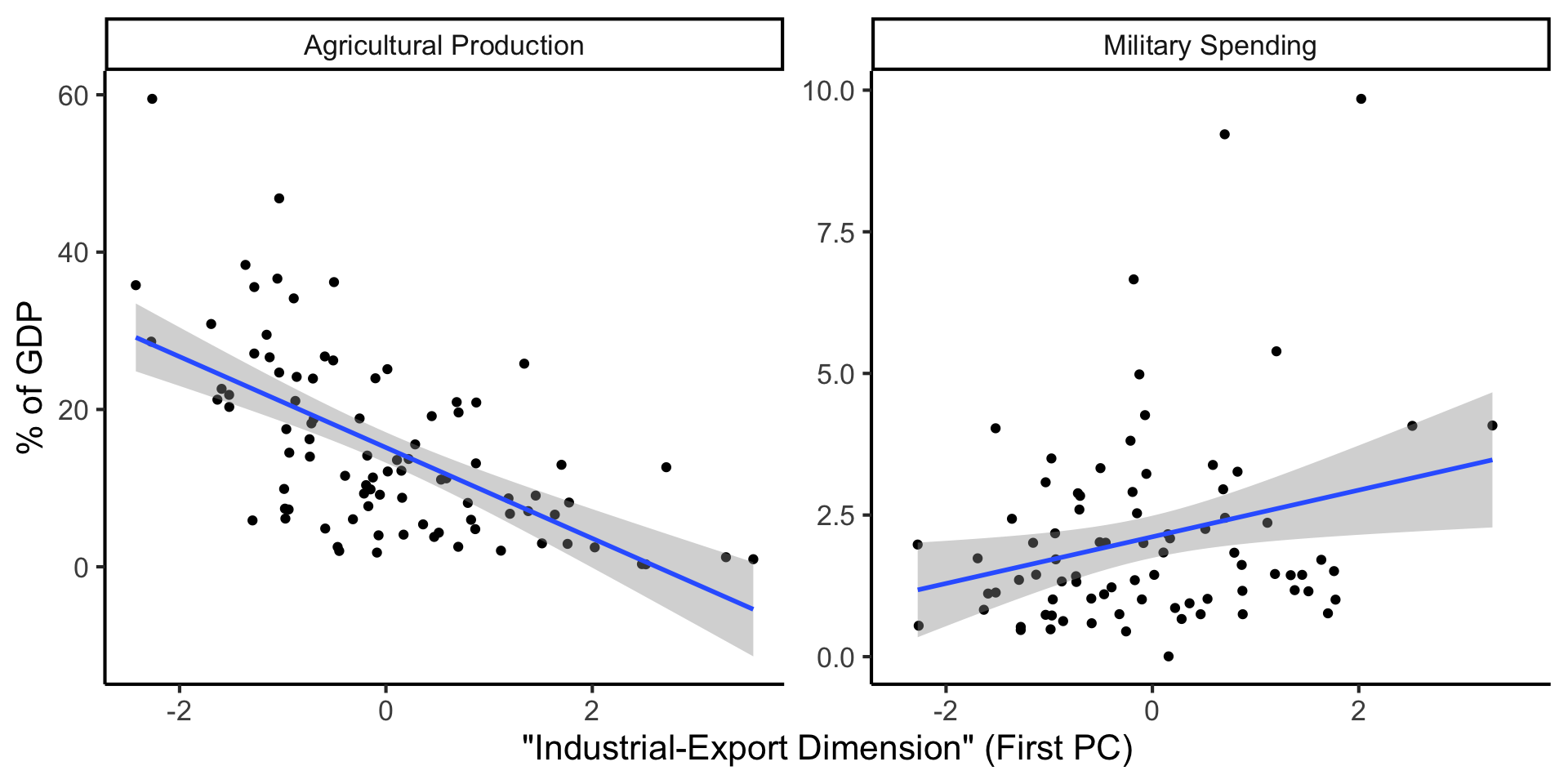

Create Your Own Dimension!

…And Use It for EDA

But in Our Case…

- \(x\) and \(y\) dimensions already have meaning, and we have a hypothesis about effect of \(x\) on \(y\)!

The Regression Hypothesis \(\mathcal{H}_{\text{reg}}\)

Given data \((X, Y)\), we estimate \(\widehat{y} = \widehat{\beta}_0 + \widehat{\beta}_1x\), hypothesizing that:

- Starting from \(y = \underbrace{\widehat{\beta}_0}_{\mathclap{\text{Intercept}}}\) when \(x = 0\),

- An increase of \(x\) by 1 unit is associated with an increase of \(y\) by \(\underbrace{\widehat{\beta}_1}_{\mathclap{\text{Coefficient}}}\) units

- We want to measure how well our line predicts \(y\) for any given \(x\) value \(\implies\) vertical distance from regression line

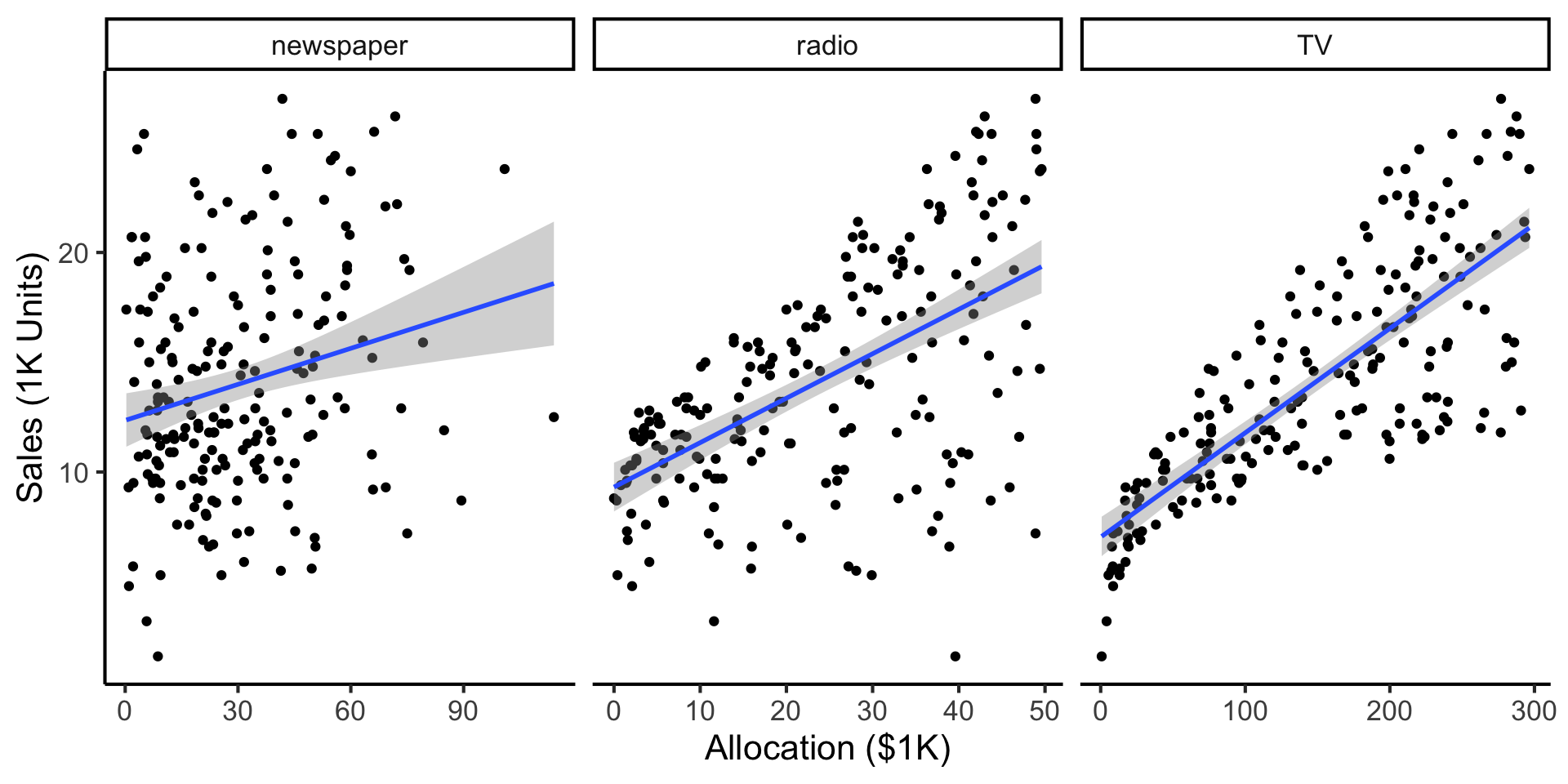

Example: Advertising Effects

- Independent variable: $ put into advertisements; Dependent variable: Sales

- Goal 1: Predict sales for a given allocation

- Goal 2: Infer best allocation for a given advertising budget (more simply: a new $1K appears! Where should we invest it?)

Simple Linear Regression

- For now, we treat Newspaper, Radio, TV advertising separately: how much do sales increase per $1 into [medium]? (Later we’ll consider them jointly: multiple regression)

Our model:

\[ Y = \underbrace{\param{\beta_0}}_{\mathclap{\text{Intercept}}} + \underbrace{\param{\beta_1}}_{\mathclap{\text{Slope}}}X + \varepsilon \]

…Generates predictions via:

\[ \widehat{y} = \underbrace{\widehat{\beta}_0}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Estimated} \\[-5mm] \text{intercept}\end{array}}} ~+~ \underbrace{\widehat{\beta}_1}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Estimated} \\[-4mm] \text{slope}\end{array}}}\cdot x \]

- Note how these predictions will be wrong (unless the data is perfectly linear)

- We’ve accounted for this in our model (by including \(\varepsilon\) term)!

- But, we’d like to find estimates \(\widehat{\beta}_0\) and \(\widehat{\beta}_1\) that produce the “least wrong” predictions: motivates focus on residuals \(\widehat{\varepsilon}_i\)…

\[ \widehat{\varepsilon}_i = \underbrace{y_i}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Real} \\[-5mm] \text{label}\end{array}}} - \underbrace{\widehat{y}_i}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Predicted} \\[-5mm] \text{label}\end{array}}} = \underbrace{y_i}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Real} \\[-5mm] \text{label}\end{array}}} - \underbrace{ \left( \widehat{\beta}_0 + \widehat{\beta}_1 \cdot x \right) }_{\text{\small{Predicted label}}} \]

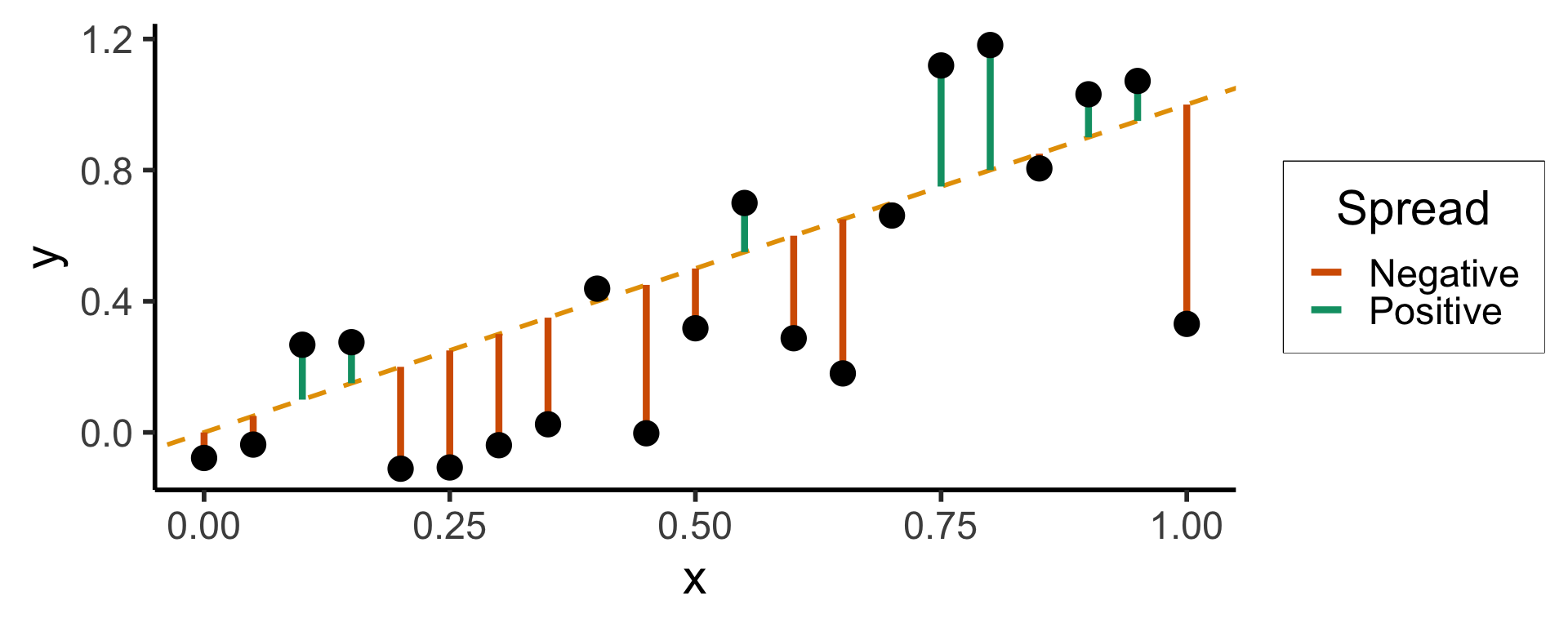

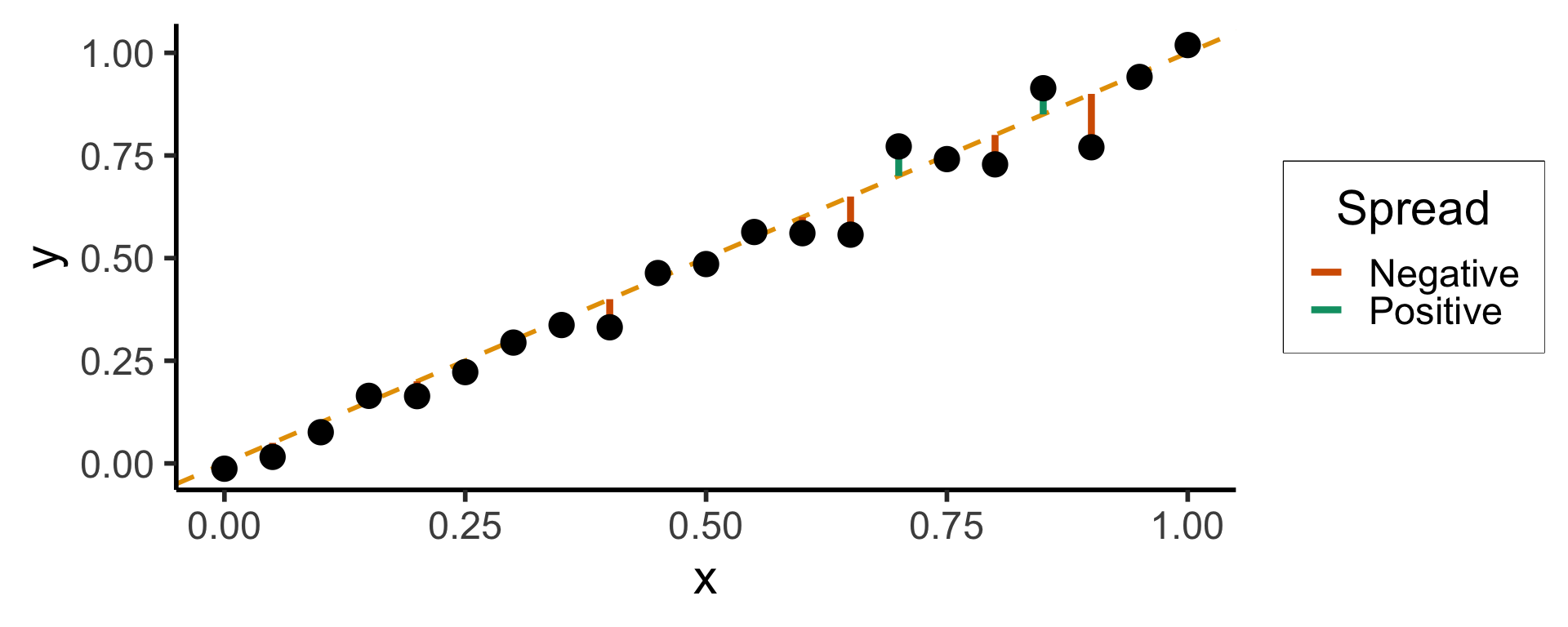

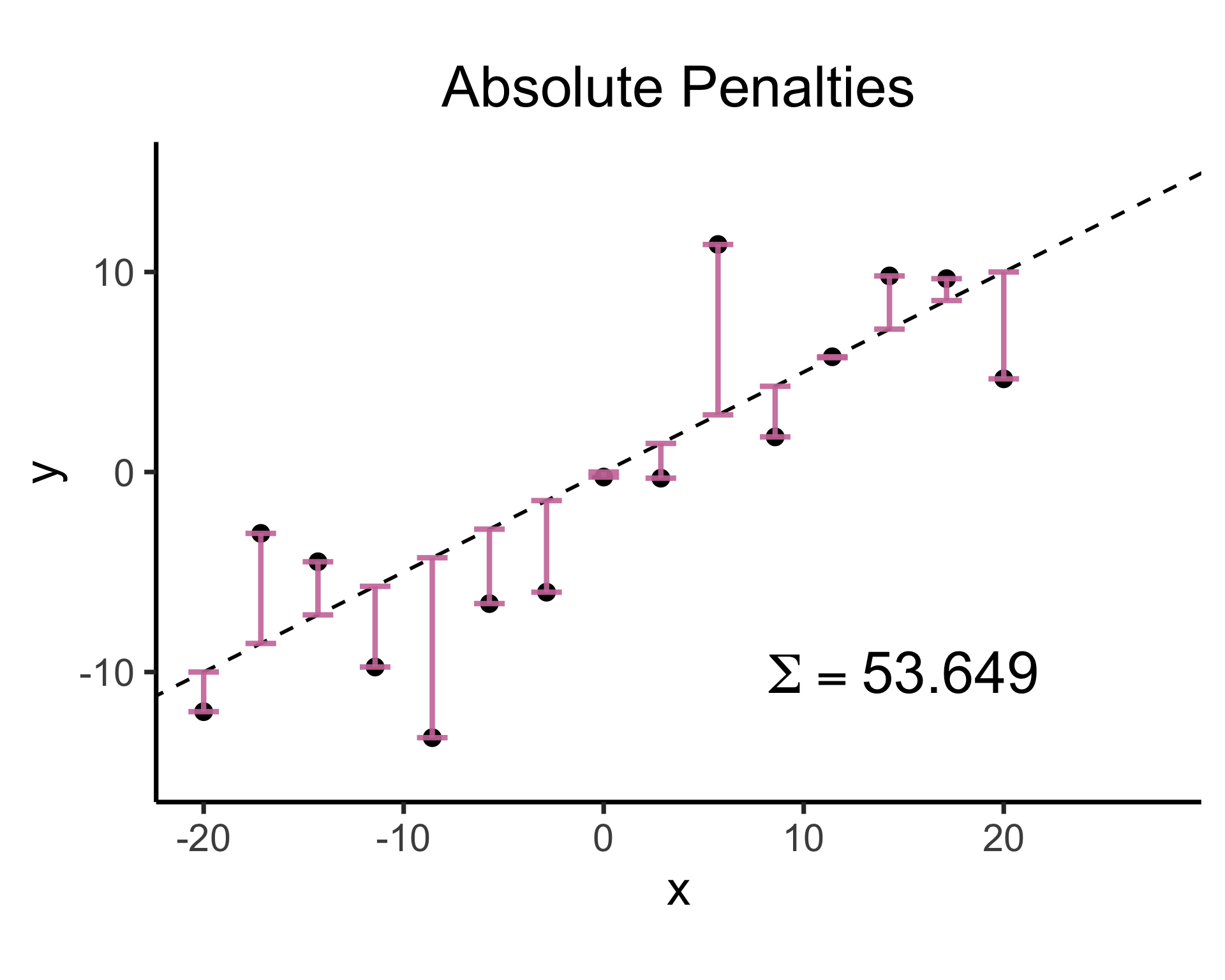

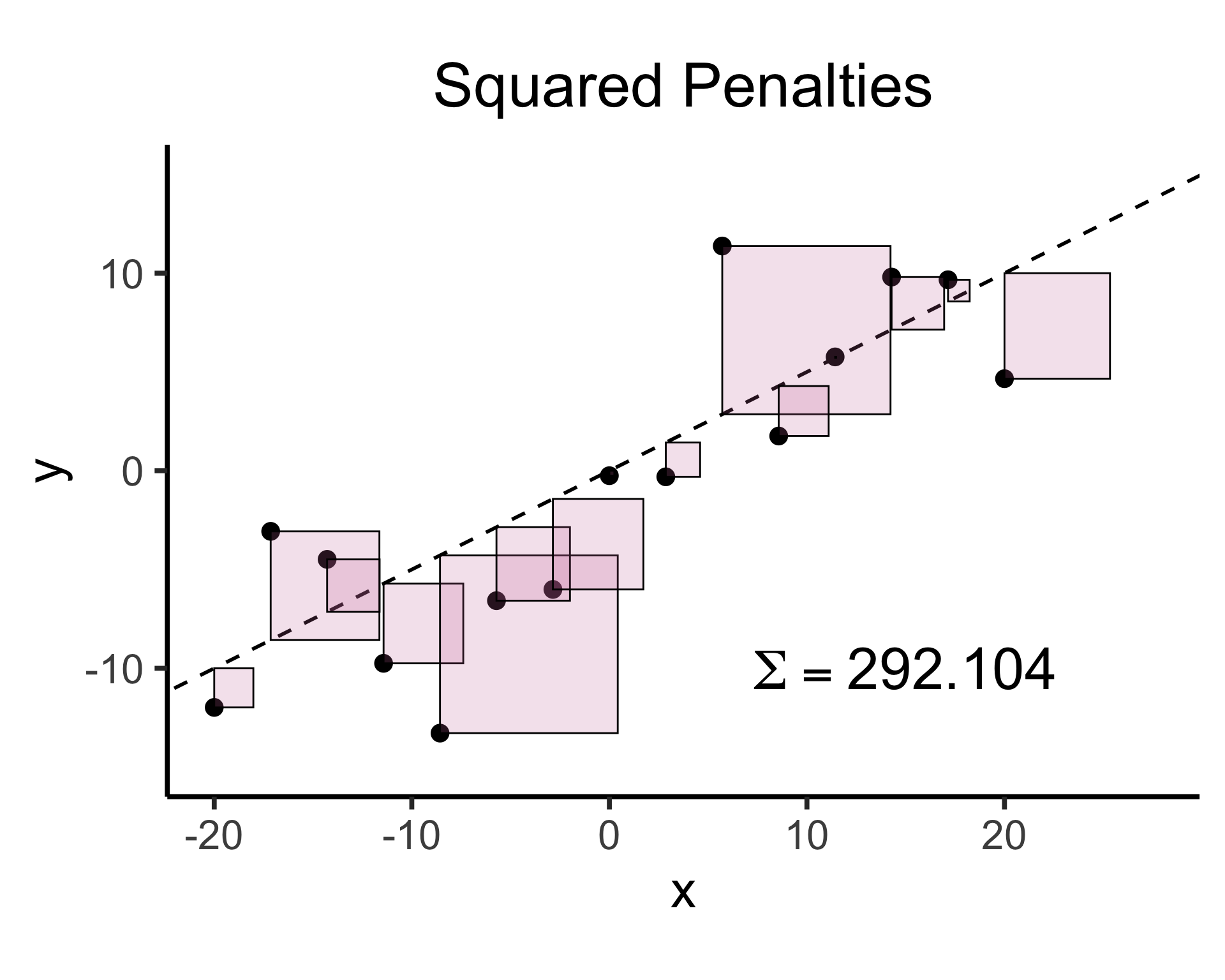

Least Squares: Minimizing Residuals

What can we optimize to ensure these residuals are as small as possible?

Sum?

0.0000000000Sum of Squares?

3.8405017200Sum of absolute vals?

7.6806094387

Sum?

0.0000000000Sum of Squares?

1.9748635217Sum of absolute vals?

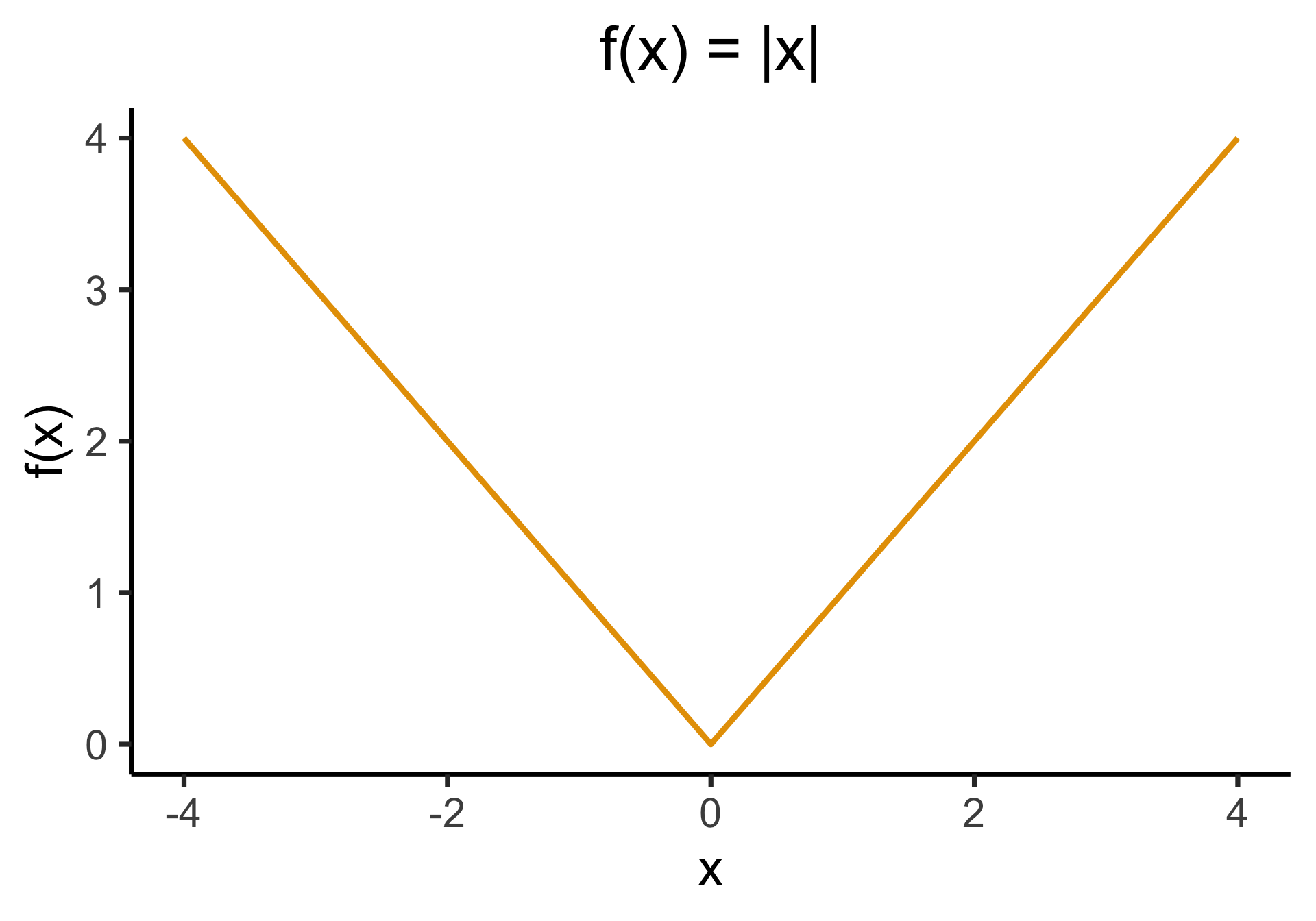

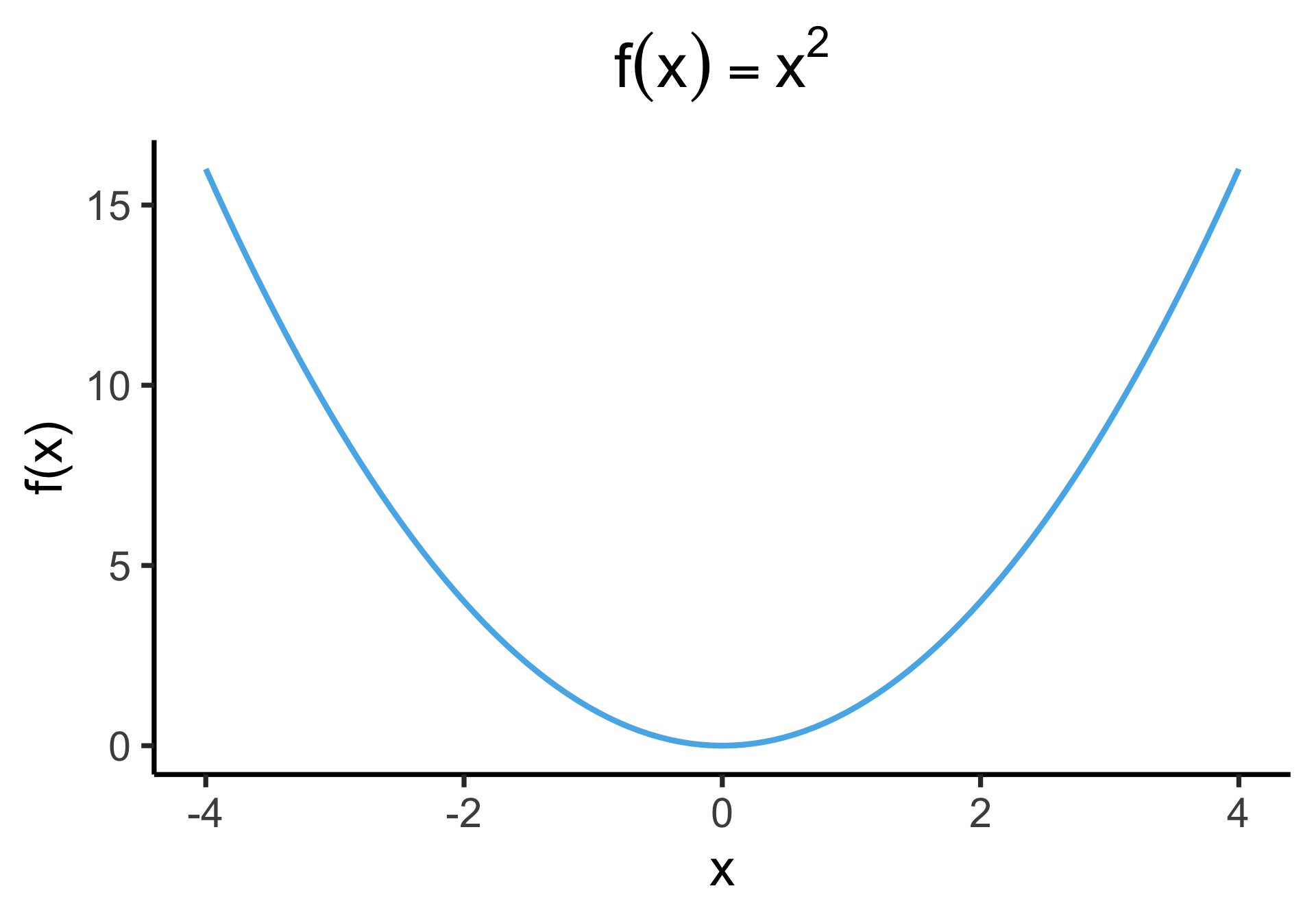

5.5149697440Why Not Absolute Value?

- Two feasible ways to prevent positive and negative residuals cancelling out:

- Absolute error \(\left|y - \widehat{y}\right|\) or squared error \(\left( y - \widehat{y} \right)^2\)

- But remember: we’re aiming to minimize 👀 these residuals; ghost of calculus past 😱

- We minimize by taking derivatives… which one is differentiable everywhere?

Outliers Penalized Quadratically

- May feel arbitrary at first (we’re “forced” to use squared error because of calculus?)

- It also has important consequences for “learnability” via gradient descent!

Key Features of Regression Line

- Regression line is BLUE: Best Linear Unbiased Estimator

- What exactly is it the “best” linear estimator of?

\[ \widehat{y} = \underbrace{\widehat{\beta}_0}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Estimated} \\[-5mm] \text{intercept}\end{array}}} ~+~ \underbrace{\widehat{\beta}_1}_{\mathclap{\small\begin{array}{c}\text{Estimated} \\[-4mm] \text{slope}\end{array}}}\cdot x \]

is chosen so that

\[ \widehat{\theta} = \left(\widehat{\beta}_0, \widehat{\beta}_1\right) = \argmin_{\beta_0, \beta_1}\left[ \sum_{x_i \in X} \left(~~\overbrace{\widehat{y}(x_i)}^{\mathclap{\small\text{Predicted }y}} - \overbrace{\expect{Y \mid X = x_i}}^{\small \text{Avg. }y\text{ when }x = x_i}\right)^{2~} \right] \]

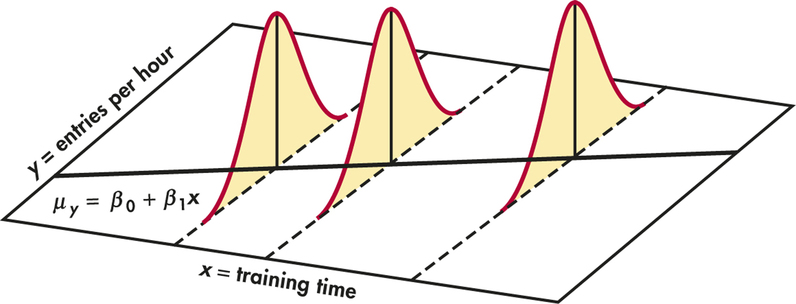

Where Did That \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x_i]\) Come From?

- From our assumption that the irreducible errors \(\varepsilon_i\) are normally distributed \(\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\)

- Kind of an immensely important point, since it gives us a hint for checking whether model assumptions hold: spread around the regression line should be \(\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\)

Heteroskedasticity

- If spread increases or decreases for larger \(x\), for example, then \(\varepsilon \nsim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\)

Figure 3.11 from James et al. (2023)

But… What About Other Types of Vars?

- 5000: you saw nominal, ordinal, cardinal vars

- 5100: you wrestled with discrete vs. continuous RVs

- Good News #1: Regression can handle all these types+more!

- Good News #2: Distinctions between classification and regression diminish as you learn fancier regression methods!

- tldr: Predict continuous probabilities \(\Pr(Y) \in [0,1]\) (regression), then guess 1 if \(\Pr(Y) > 0.5\) (classification)

- By end of 5300 you should have something on your toolbelt for handling most cases like “I want to do [regression / classification], but my data is [not cardinal+continuous]”

Quiz Review

Objective Functions

“Fitting” a statistical model to data means minimizing some loss function that measures “how bad” our predictions are:

Optimization Problems: General Form

Find \(x^*\), the solution to

\[ \begin{align} \min_{x} ~ & f(x) &\text{(Objective function)} \\ \text{s.t. } ~ & g(x) = 0 &\text{(Constraints)} \end{align} \]

- Earlier we were able to write \(x^* = \argmax_x{f(x)}\), since there were no constraints. Is there a way to write a formula like this with constraints?

- Answer: Yes! Thx Giuseppe-Luigi Lagrangia = Joseph-Louis Lagrange:

\[ x^* = \argmax_{x,~\lambda}f(x) - \lambda[g(x)] \]

Example Problem

Example 1: Unconstrained Optimization

Find \(x^*\), the solution to

\[ \begin{align} \min_{x} ~ & f(x) = 3x^2 - x \\ \text{s.t. } ~ & \varnothing \end{align} \]

Our Plan

- Compute the derivative \(f'(x) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}f(x)\),

- Set it equal to zero: \(f'(x) = 0\), and

- Solve this equality for \(x\), i.e., find values \(x^*\) satisfying \(f'(x^*) = 0\)

Computing the derivative:

\[ f'(x) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}f(x) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left[3x^2 - x\right] = 6x - 1, \]

Solving for \(x^*\), the value(s) satisfying \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}f'(x^*) = 0\) for just-derived \(f'(x)\):

\[ f'(x^*) = 0 \iff 6x^* - 1 = 0 \iff x^* = \frac{1}{6}. \]

Derivative Cheatsheet

| Type of Thing | Thing | Change in Thing when \(x\) Changes by Tiny Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Polynomial | \(f(x) = x^n\) | \(f'(x) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}f(x) = nx^{n-1}\) |

| Fraction | \(f(x) = \frac{1}{x}\) | Use Polynomial rule (since \(\frac{1}{x} = x^{-1}\)) to get \(f'(x) = -\frac{1}{x^2}\) |

| Logarithm | \(f(x) = \ln(x)\) | \(f'(x) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x} = \frac{1}{x}\) |

| Exponential | \(f(x) = e^x\) | \(f'(x) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}e^x = e^x\) (🧐❗️) |

| Multiplication | \(f(x) = g(x)h(x)\) | \(f'(x) = g'(x)h(x) + g(x)h'(x)\) |

| Division | \(f(x) = \frac{g(x)}{h(x)}\) | Too hard to memorize… turn it into Multiplication, as \(f(x) = g(x)(h(x))^{-1}\) |

| Composition (Chain Rule) | \(f(x) = g(h(x))\) | \(f'(x) = g'(h(x))h'(x)\) |

| Fancy Logarithm | \(f(x) = \ln(g(x))\) | \(f'(x) = \frac{g'(x)}{g(x)}\) by Chain Rule |

| Fancy Exponential | \(f(x) = e^{g(x)}\) | \(f'(x) = g'(x)e^{g(x)}\) by Chain Rule |

References

DSAN 5300 Week 2: Linear Regression