Week 1: Introduction to the Course

DSAN 5300: Statistical Learning

Spring 2026, Georgetown University

Section 01 (Tuesdays)jh2343@georgetown.edu

Section 02 (Mondays)jj1088@georgetown.edu

Section 03 (Fridays)az692@georgetown.edu

Wednesday, January 7, 2026

Schedule

Today’s Planned Schedule:

| Start | End | Topic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lecture | 6:30pm | 7:30pm | What Does It Mean to Learn? → |

| 7:30pm | 8:00pm | Nonlinear Learning → | |

| Break! | 8:00pm | 8:10pm | |

| 8:10pm | 8:40pm | Statistical Modeling → | |

| 8:40pm | 9:00pm | Bias-Variance Tradeoff → |

What Does It Mean to Learn?

Spoiler: For both humans and computers,

learning \(\neq\) memorization!

\[ \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmax}{argmax} \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmin}{argmin} \newcommand{\bigexp}[1]{\exp\mkern-4mu\left[ #1 \right]} \newcommand{\bigexpect}[1]{\mathbb{E}\mkern-4mu \left[ #1 \right]} \newcommand{\definedas}{\overset{\small\text{def}}{=}} \newcommand{\definedalign}{\overset{\phantom{\text{defn}}}{=}} \newcommand{\eqeventual}{\overset{\text{eventually}}{=}} \newcommand{\Err}{\text{Err}} \newcommand{\expect}[1]{\mathbb{E}[#1]} \newcommand{\expectsq}[1]{\mathbb{E}^2[#1]} \newcommand{\fw}[1]{\texttt{#1}} \newcommand{\given}{\mid} \newcommand{\green}[1]{\color{green}{#1}} \newcommand{\heads}{\outcome{heads}} \newcommand{\iid}{\overset{\text{\small{iid}}}{\sim}} \newcommand{\lik}{\mathcal{L}} \newcommand{\loglik}{\ell} \DeclareMathOperator*{\maximize}{maximize} \DeclareMathOperator*{\minimize}{minimize} \newcommand{\mle}{\textsf{ML}} \newcommand{\nimplies}{\;\not\!\!\!\!\implies} \newcommand{\orange}[1]{\color{orange}{#1}} \newcommand{\outcome}[1]{\textsf{#1}} \newcommand{\param}[1]{{\color{purple} #1}} \newcommand{\pgsamplespace}{\{\green{1},\green{2},\green{3},\purp{4},\purp{5},\purp{6}\}} \newcommand{\pedge}[2]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{~{#1}~} \rightarrow \; \enclose{circle}{\kern.01em {#2}~\kern.01em}} \newcommand{\pnode}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{\kern.1em {#1} \kern.1em}} \newcommand{\ponode}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{box}[background=lightgray]{{#1}}} \newcommand{\pnodesp}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{~{#1}~}} \newcommand{\purp}[1]{\color{purple}{#1}} \newcommand{\sign}{\text{Sign}} \newcommand{\spacecap}{\; \cap \;} \newcommand{\spacewedge}{\; \wedge \;} \newcommand{\tails}{\outcome{tails}} \newcommand{\Var}[1]{\text{Var}[#1]} \newcommand{\bigVar}[1]{\text{Var}\mkern-4mu \left[ #1 \right]} \]

Memorizing vs. Learning

| Question 1 | How many sentences have you heard (as input) in your life? | Answer: Finitely many… 🤔 |

| Question 2 | How many sentences could you generate (as output) right now? |

Answer: Infinitely many… 🤯 (“My favorite number is 1”, “My favorite number is 2”, …) |

| Question 3 | How is this possible? | Answer: Our brains infer the “deep structure” of language, a generative model, from our linguistic inputs |

Our brains learn a grammar…

| S | \(\rightarrow\) | NP VP |

| NP | \(\rightarrow\) | DetP N | AdjP NP |

| VP | \(\rightarrow\) | V NP |

| AdjP | \(\rightarrow\) | Adj | Adv AdjP |

| N | \(\rightarrow\) | frog | tadpole |

| V | \(\rightarrow\) | sees | likes |

| Adj | \(\rightarrow\) | big | small | tiny |

| Adv | \(\rightarrow\) | very | immensely |

| DetP | \(\rightarrow\) | a | the |

…For generating arbitrary (infinitely many!) sentences

\(\leadsto\) Our Goal This Semester

The Goal of Statistical Learning (V1)

| Given… | Find… |

|---|---|

|

|

Note that we’ll often think of the dataset \(\mathfrak{D}\) as being in matrix/vector form:

\[ \mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{x}_1 \\ \mathbf{x}_2 \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{x}_n \end{pmatrix} = \underbrace{ \begin{pmatrix} x_{1,1} & x_{1,2} & \cdots & x_{1,p} \\ x_{2,1} & x_{2,2} & \cdots & x_{2,p} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_{n,1} & x_{n,2} & \cdots & x_{n,p} \end{pmatrix} }_{n \times p \textbf{ Feature Matrix}} , \mathbf{y} = \underbrace{ \begin{pmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ \vdots \\ y_n \end{pmatrix} }_{\mathclap{\text{Length }n \text{ Label Vector}}} \]

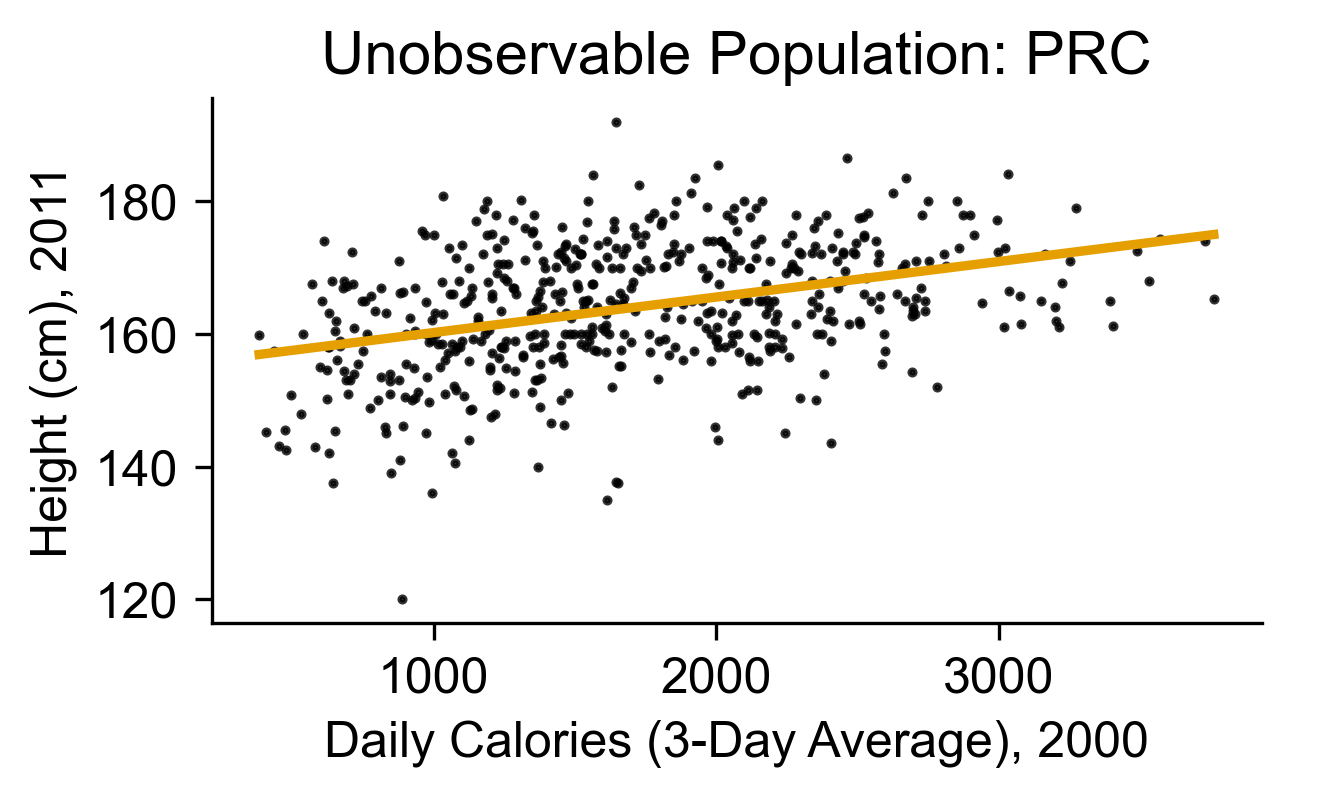

Why “Not Yet Observed”? (Real Data!)

Data from China Health and Nutrition Survey

Code

chns_df = pd.read_csv("data/chns_2000_2011.csv")

# First use statmodels to get the intercept and slope for pop

height_model_result = smf.ols(

formula='height_cm_2011 ~ daily_calories_2000',

data=chns_df

).fit()

ols_params = height_model_result.params

ols_int = ols_params['Intercept']

ols_slope = ols_params['daily_calories_2000']

x_mean = chns_df['daily_calories_2000'].mean()

ols_at_mean = ols_int + ols_slope * x_mean

chns_df.head(4)| IDind | daily_calories_2000 | daily_calories_2011 | height_cm_2000 | height_cm_2011 | age_2000 | age_2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 211101008005 | 2267.826467 | 2286.613966 | 162.0 | 175.0 | 12.0 | 24.0 |

| 1 | 211101008061 | 1671.856407 | 2166.041310 | 120.2 | 172.0 | 6.0 | 17.0 |

| 2 | 211103013003 | 1884.064868 | 1385.503177 | 163.0 | 164.5 | 17.0 | 28.0 |

| 3 | 211104001004 | 3394.813400 | 1526.421314 | 142.0 | 165.0 | 12.0 | 23.0 |

Code

cal_label = "Daily Calories (3-Day Average), 2000"

height_label = "Height (cm), 2011"

ax = pw.Brick(figsize=(3.5,1.75))

height_plot = sns.regplot(

chns_df,

x='daily_calories_2000', y='height_cm_2011',

ci=None,

color='black',

scatter_kws={'s': 2},

line_kws=dict(color='#E69F00'),

ax=ax

);

ax.set_title(f"Unobservable Population: PRC");

ax.set_xlabel(cal_label);

ax.set_ylabel(height_label);

ax.spines['right'].set_visible(False);

ax.spines['top'].set_visible(False);

ax

Code

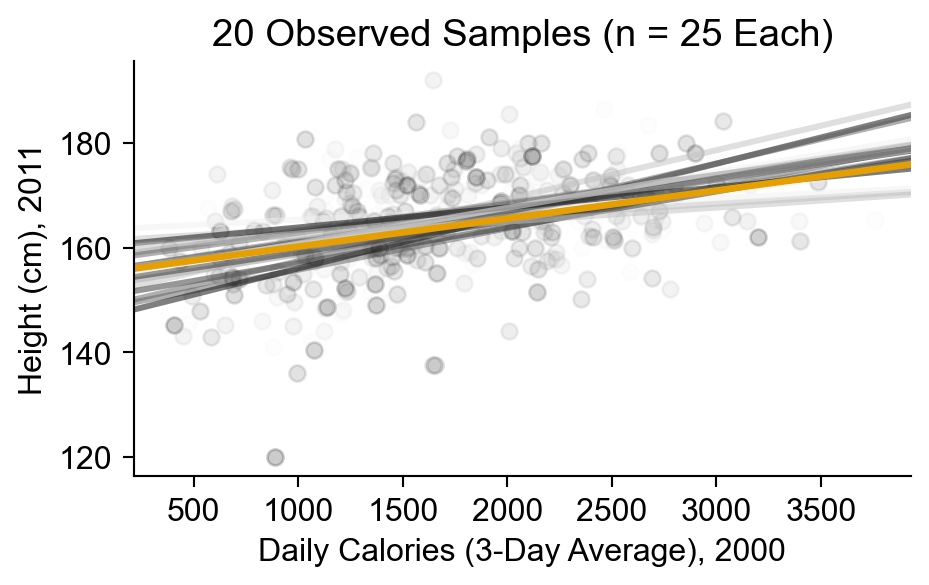

sample_size = 25

num_samples = 20

sample_dfs = []

seed_start = 5310

for cur_seed in range(seed_start, seed_start+num_samples):

cur_sample_df = chns_df.sample(

n = sample_size, random_state=cur_seed

)

cur_sample_df['sample_num'] = cur_seed - seed_start

sample_dfs.append(cur_sample_df)

combined_df = pd.concat(sample_dfs, ignore_index=True)

# frame = pw.Brick(figsize=(4,3))

sample_plot = sns.lmplot(

combined_df,

x='daily_calories_2000', y='height_cm_2011',

hue='sample_num', ci=None,

palette=sns.color_palette("light:#000"),

# palette='Greys',

aspect=1.67, height=3,

scatter_kws={'alpha': 0.1},

line_kws={'alpha': 0.5},

truncate=False,

legend=None,

);

sample_plot.ax.axline(

xy1=(x_mean,ols_at_mean),

slope=ols_slope,

color='#E69F00',

lw=2.5,

)

sample_plot.ax.set_title(f"{num_samples} Observed Samples (n = {sample_size} Each)");

sample_plot.set_xlabels(cal_label);

sample_plot.set_ylabels(height_label);

plt.show()

- Which line is “correct”? We don’t know! Samples may not arrive until the future!

- \(\leadsto\) We need to incorporate uncertainty about the future into our model

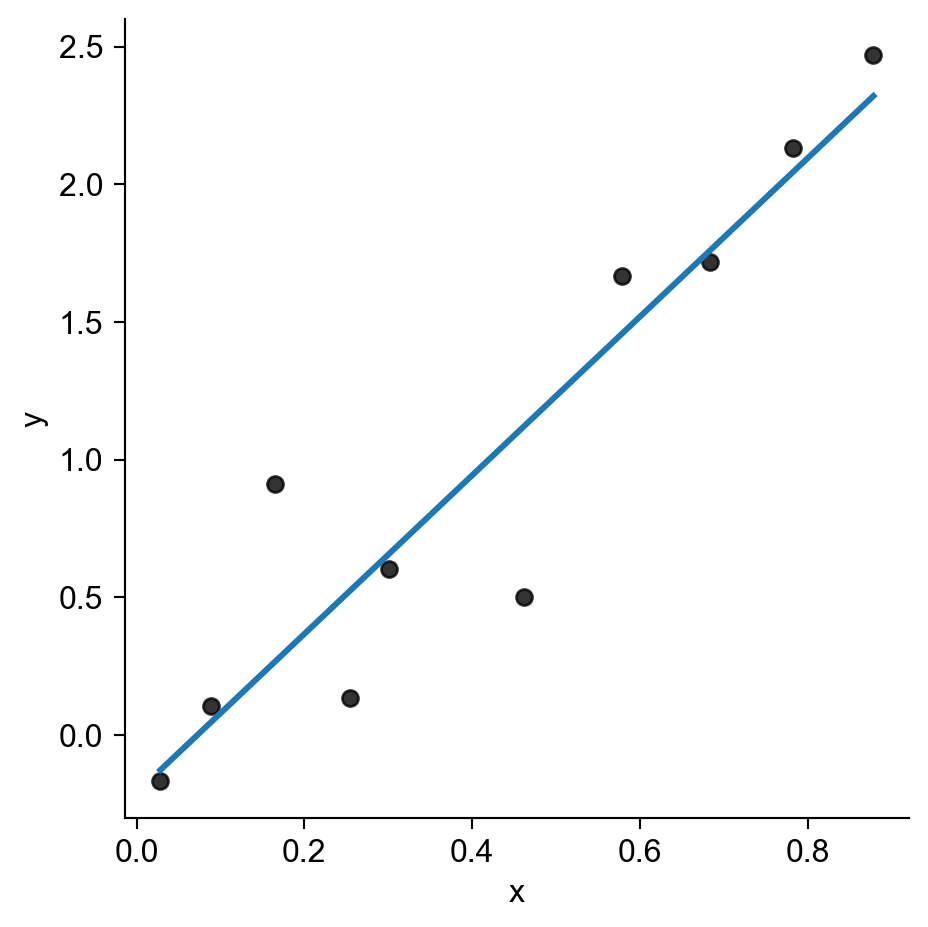

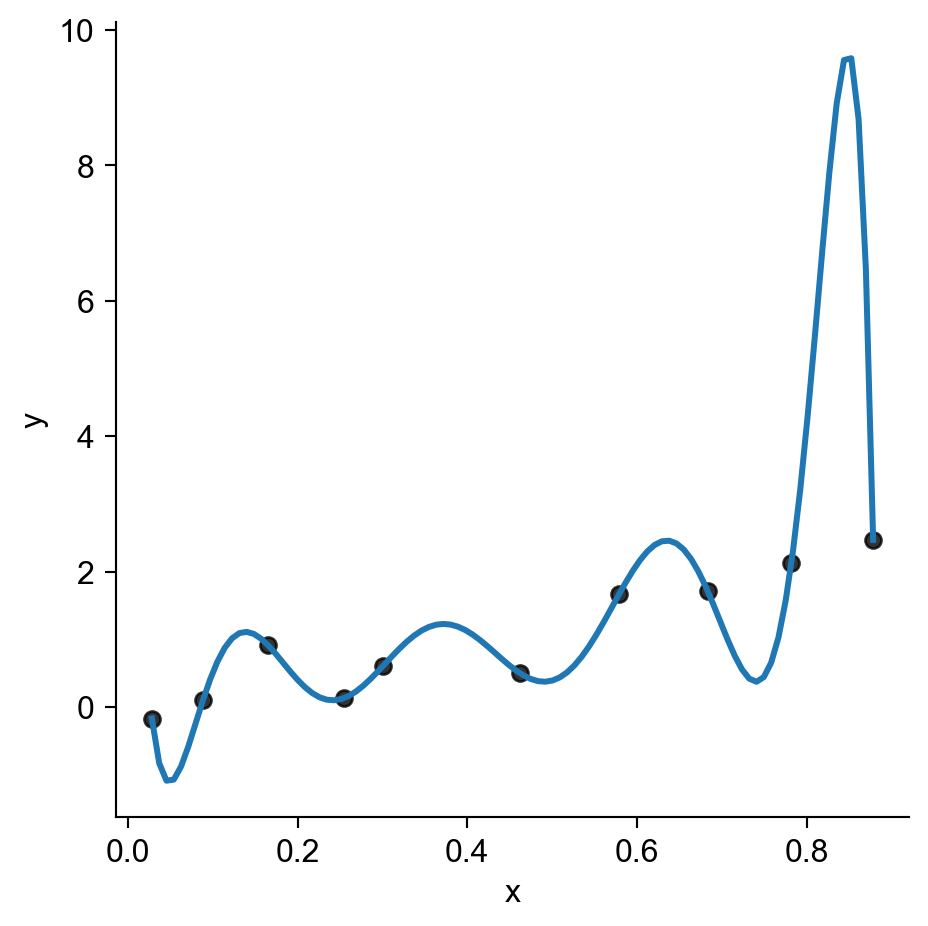

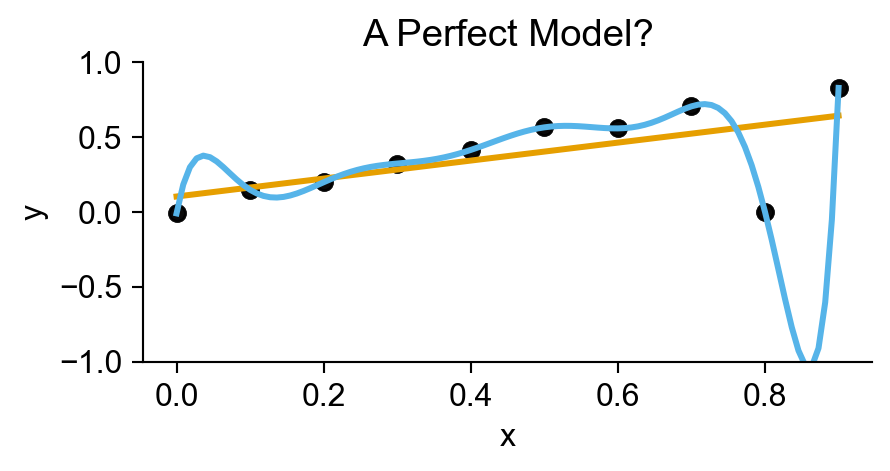

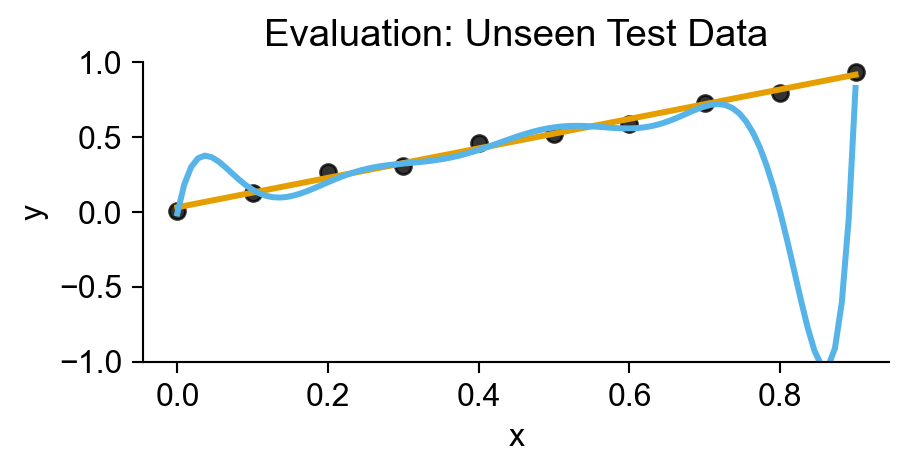

Nonlinear Learning

- An even messier complication: what happens if we consider prediction functions that aren’t just straight lines?

- The evil scourge of… OVERFITTING

Computers “Learning” = Computers Obediently Following Orders

Code

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed=5302)

n = 10

x_vals = rng.uniform(size=n, low=0, high=1)

y_vals_raw = 3 * x_vals

y_noise = rng.normal(size=n, loc=0, scale=0.5)

y_vals = y_vals_raw + y_noise

data_df = pd.DataFrame({'x': x_vals, 'y': y_vals})

sns.lmplot(

data_df,

x='x', y='y',

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

ci=None

)

sns.lmplot(

data_df,

x='x', y='y',

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

order=n,

ci=None

)

5000: Accuracy \(\leadsto\) 5300: Generalization

- Training Accuracy: How well does it fit the data we can see?

- Test Accuracy: How well does it generalize to future data?

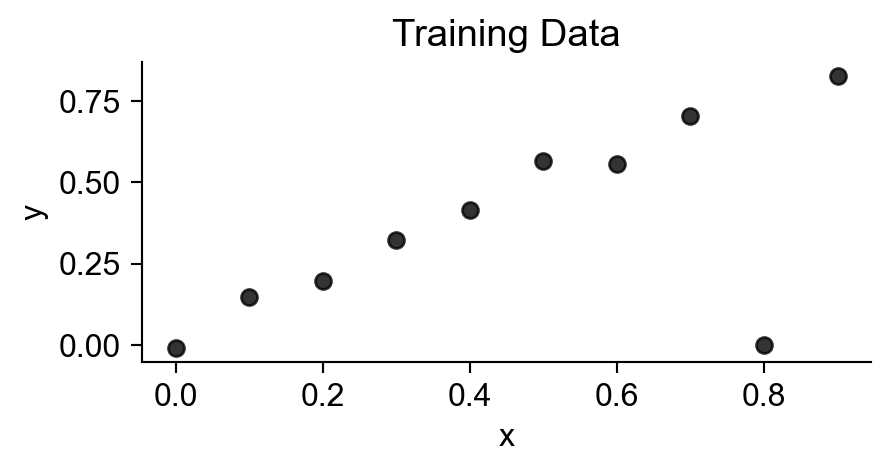

Code

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

x = np.arange(0, 1, 0.1)

n = len(x)

eps = rng.normal(size=n, loc=0, scale=0.04)

y = x + eps

# But make one big outlier

midpoint = int(np.ceil((3/4)*n))

y[midpoint] = 0

of_df = pd.DataFrame({'x': x, 'y': y})

# Linear model

# lin_model = smf.ols(formula='y ~ x', data=of_data)

train_plot = sns.lmplot(

data=of_df,

x='x', y='y',

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

ci=None,

fit_reg=False,

height=2.4,

aspect=2,

)

plt.title("Training Data");

plt.show()

# Data setup

x_test = np.arange(0, 1, 0.1)

n_test = len(x_test)

eps_test = rng.normal(size=n_test, loc=0, scale=0.04)

y_test = x_test + eps_test

of_test_df = pd.DataFrame({'x': x_test, 'y': y_test})

test_points_plot = sns.lmplot(

data=of_df,

x='x', y='y',

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

line_kws=dict(color=cb_palette[0]),

ci=None,

height=2.4,

aspect=2,

fit_reg=False,

);

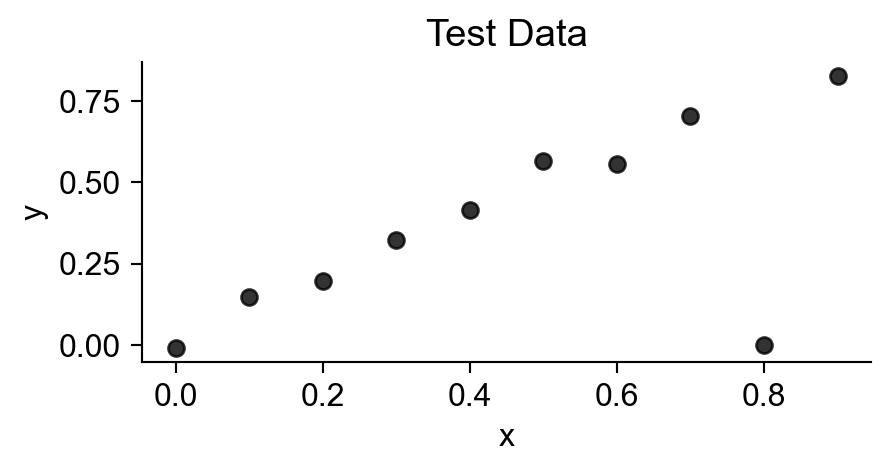

plt.title("Test Data");

plt.show()

perfect_plot = sns.lmplot(

data=of_df,

x='x', y='y',

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

line_kws=dict(color=cb_palette[0]),

ci=None,

height=2.4,

aspect=2,

)

perfect_plot.ax.set_ylim(-1, 1);

sns.regplot(

data=of_df,

x='x', y='y',

order=n,

ci=None,

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

line_kws=dict(color=cb_palette[1])

)

plt.title("A Perfect Model?");

plt.show()

test_plot = sns.lmplot(

data=of_test_df,

x='x', y='y',

ci=None,

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

line_kws=dict(color=cb_palette[0]),

height=2.4, aspect=2,

);

test_plot.ax.set_ylim(-1, 1);

sns.regplot(

data=of_df,

x='x', y='y',

order=n,

ci=None,

scatter_kws=dict(color='black'),

line_kws=dict(color=cb_palette[1]),

marker='',

);

plt.title("Evaluation: Unseen Test Data");

plt.show()

Statistical Modeling

So far:

Our models need to accommodate irreducible error (error inherent to DGP)

Our models need to penalize complexity, to prevent Yes Man from just “memorizing” training data

…But, if we penalize too harshly, we lose the ability to model nonlinearity!

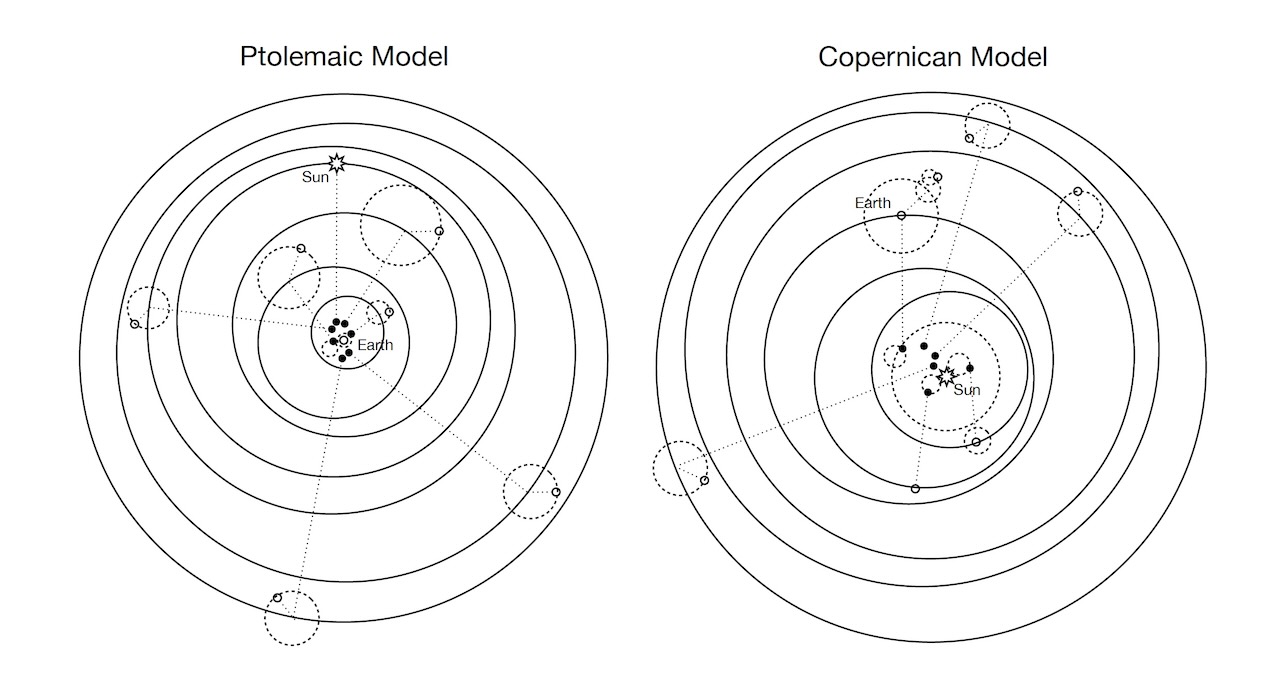

Let’s dive a bit more into , via one of my fav examples from the history of science 🤓

Scientific Models

Ptolemaic model: wrong? or just “less good” than Copernican model? How so?1

Prediction vs. Understanding

Both models “predict” Mars’ orbit relative to us equally well – why might we still prefer geocentric model? (Hint: How many parameters does each require?)

Adapted from Michael Fowler’s Lecture Notes

Bias-Variance Tradeoff

- (Why there’s “no free lunch”: we can’t [easily] just ask a computer to find the “best” model for our data)

Why Statistical Learning?

- Answer: Statistical theory provides us with guarantees about (e.g.) convergence or unbiasedness of our estimates

- Example next week: regression line estimated via OLS is Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE)

- As we move from linear \(\leadsto\) non-linear models we start losing guarantees like “This method produces the best estimate of \(\underline{\hspace{40mm}}\)”

Bias-Variance Decomposition

Model errors can be decomposed into three components:

Model bias: Mismatch between DGP and model prediction

(too simple [lines for nonlinear DGP] or too complex [wiggly function for linear DGP])

Model variance: Sensitivity to re-draws from DGP

Unavoidable error inherent in the DGP

\[ \mathbb{E}\mkern-4mu\left[ \left( y_0 - \widehat{f}(x_0) \right)^2 \right] = \left[ \text{Bias}\mkern-2mu\left( \hat{f}(x_0) \right) \right]^2 + \text{Var}\mkern-2mu\left[ \hat{f}(x_0) \right] + \text{Var}[\varepsilon] \]

(James et al. (2023), pg. 32!)

Consequence: “No Free Lunch”!

True DGP: Polynomial

True DGP: Linear

True DGP: Highly Nonlinear

Squared bias (blue), variance (orange), unavoidable error (dashed line), and test MSE (red) for the three data sets in Chapter 1 of James et al. (2023), pg. 33

References

DSAN 5300 Week 1: Course Intro