[1, 4, 4]Week 6: Introduction to Spark

DSAN 6000: Big Data and Cloud Computing

Fall 2025

Amit Arora and Jeff Jacobs

Monday, September 29, 2025

Highest-Level Overview (Roadmap!)

- Week 3: Map-Reduce

- But, just the “plain”, basic version built into Python (

map(),functools.reduce())

- But, just the “plain”, basic version built into Python (

- Last Week: Athena with AWS Glue under the hood

- “Automated” ETL Pipeline!

- This Week: Hitting a wall with Athena… It doesn’t know in advance what [types of] queries you’re going to make!

- If you’re going to group by (e.g.) state, then rent 50 computers to process one state each, Athena doesn’t know to place the Ohio data on the Ohio computer!

- We need a way to “steer” Map-Reduce’s choices… Enter Hadoop MapReduce!

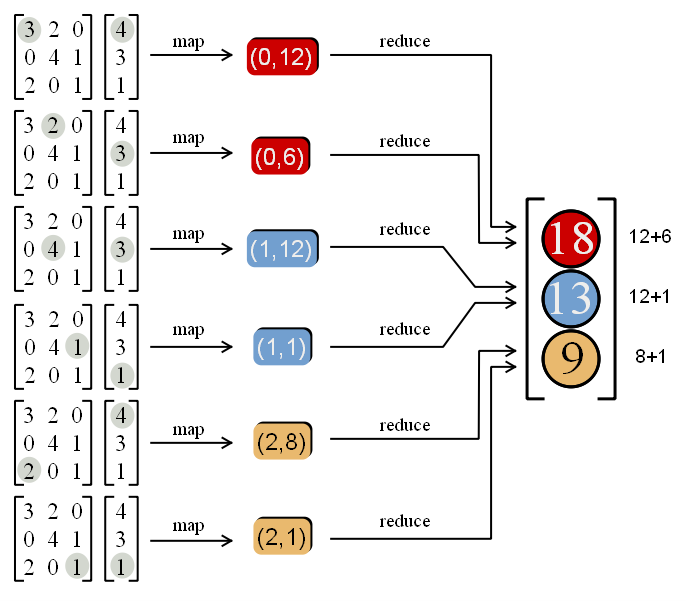

A Reminder: Map-Reduce as a Paradigm

What Happens When Not Embarrassingly Parallel?

- Think of the difference between linear and quadratic equations in algebra:

- \(3x - 1 = 0\) is “embarrassingly” solvable, on its own: you can solve it directly, by adding 3 to both sides \(\implies x = \frac{1}{3}\). Same for \(2x + 3 = 0 \implies x = -\frac{3}{2}\)

- Now consider \(6x^2 + 7x - 3 = 0\): Harder to solve “directly”, so your instinct might be to turn to the laborious quadratic equation:

\[ \begin{align*} x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} = \frac{-7 \pm \sqrt{49 - 4(6)(-3)}}{2(6)} = \frac{-7 \pm 11}{12} = \left\{\frac{1}{3},-\frac{3}{2}\right\} \end{align*} \]

- And yet, \(6x^2 + 7x - 3 = (3x - 1)(2x + 3)\), meaning that we could have split the problem into two “embarrassingly” solvable pieces, then multiplied to get result!

The Analogy to Map-Reduce

| \(\leadsto\) If code is not embarrassingly parallel (instinctually requiring laborious serial execution), | \(\underbrace{6x^2 + 7x - 3 = 0}_{\text{Solve using Quadratic Eqn}}\) |

| But can be split into… | \((3x - 1)(2x + 3) = 0\) |

| Embarrassingly parallel pieces which combine to same result, | \(\underbrace{3x - 1 = 0}_{\text{Solve directly}}, \underbrace{2x + 3 = 0}_{\text{Solve directly}}\) |

| We can use map-reduce to achieve ultra speedup (running “pieces” on GPU!) | \(\underbrace{(3x-1)(2x+3) = 0}_{\text{Solutions satisfy this product}}\) |

“Factoring” into Embarrassing and Non-Embarrassing Pieces

- Problem from DSAN 5000/5100: Computing SSR (Sum of Squared Residuals)

- \(y = (1,3,2), \widehat{y} = (2, 5, 0) \implies \text{SSR} = (1-2)^2 + (3-5)^2 + (2-0)^2 = 9\)

- Computing pieces separately:

- Combining solved pieces

9But… Why is All This Weird Mapping and Reducing Necessary?

- Without knowing a bit more of the internals of computing efficiency, it may seem like a huge cost in terms of overly-complicated overhead, not to mention learning curve…

The “Killer Application”: Matrix Multiplication

- (I learned from Jeff Ullman, who did the obnoxious Stanford thing of mentioning in passing how “two previous students in the class did this for a cool final project on web crawling and, well, it escalated quickly”, aka became Google)

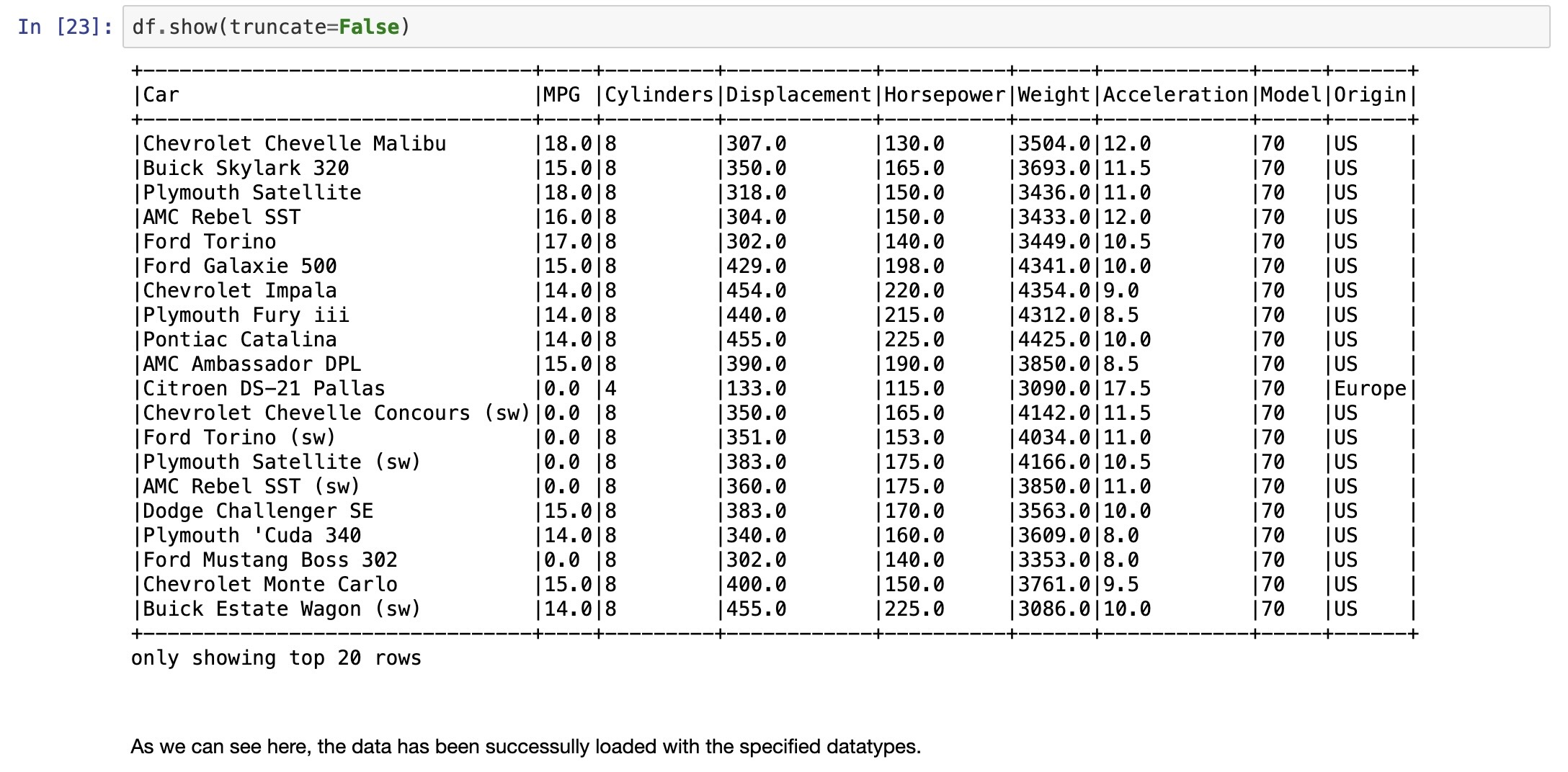

From Leskovec, Rajaraman, and Ullman (2014), which is (legally) free online!

The Killer Way-To-Learn: Text Counts!

- (2014): Text counts (2.2) \(\rightarrow\) Matrix multiplication (2.3) \(\rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow\) PageRank (5.1)

- (And yall thought it was just busywork for HW3 😏)

- The goal: User searches “Denzel Curry”… How relevant is a given webpage?

- Scenario 1: Entire internet fits on CPU \(\Rightarrow\) Can just make a big big hash table:

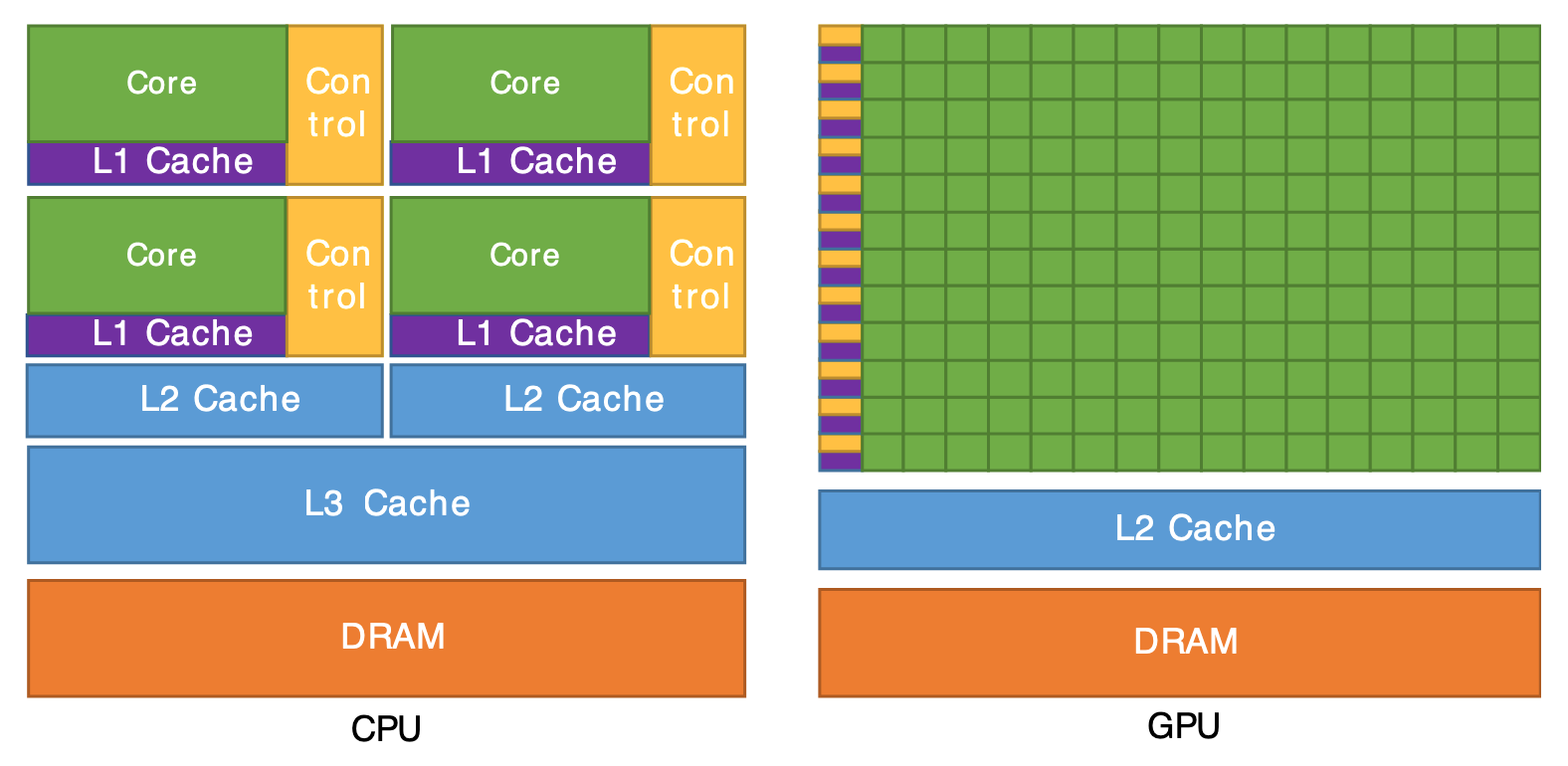

If Everything Doesn’t Fit on CPU…

From Cornell Virtual Workshop, “Understanding GPU Architecture”

Break Problem into Chunks for the Green Bois!

- \(\implies\) Total = \(O(3n) = O(n)\)

- But also optimized in terms of constants, because of sequential memory reads

In-Class Demo 1

In-Class Demo 2

In-Class Demo 3

Lab Time!

References

Leskovec, Jure, Anand Rajaraman, and Jeffrey David Ullman. 2014. Mining of Massive Datasets. Cambridge University Press. http://infolab.stanford.edu/~ullman/mmds/book.pdf.

DSAN 6000 Week 6: Spark