NoneTypeWeek 2: Software Design Patterns and Object-Oriented Programming

DSAN 5500: Data Structures, Objects, and Algorithms in Python

Thursday, January 15, 2026

Where We Left Off: Primitive Types

None

\[ \underset{\text{\small{Always 0}}}{\underline{\hspace{16mm}}} \]

Boolean (True or False)

\[ \underset{\{0,1\}}{\underline{\hspace{12mm}}} \]

Numbers (int, float)

\[ \small{\underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}~ \underset{\small{\{0,1\}}}{\underline{\hspace{8mm}}}} \]

- Why do we distinguish these from all other types? Computer knows in advance how much space they’ll take up! (

None: 1 bit,bool: 1 bit,int: 32/64 bits)

Primitive Types: Python Weirdness Edition

None: 1 bit (Always 0)

Boolean (True or False): Exactly 1 bit (0 or 1)

int: 32 or 64 bits (depending on OS)

Why is this happening?

Stack and Heap in C / Java

Stack and Heap in Python

Side-by-Side

Algorithmic Thinking

- What are the inputs?

- What are the outputs?

- Standard cases vs. corner cases

- Adversarial development: brainstorm all of the ways an evil hacker might break your code!

Example: Finding An Item Within A List

- Seems straightforward, right? Given a list

l, and a valuev, return the index oflwhich containsv - Corner cases galore…

- What if

lcontainsvmore than once? What if it doesn’t containvat all? What iflisNone? What ifvisNone? What iflisn’t a list at all? What ifvis itself a list?

Corner Cases

- Most people stand in the center of a room…

- Eccentric weirdos stand in the corner

- Your algorithm needs to handle all people

Demo

Data Structures: Motivation

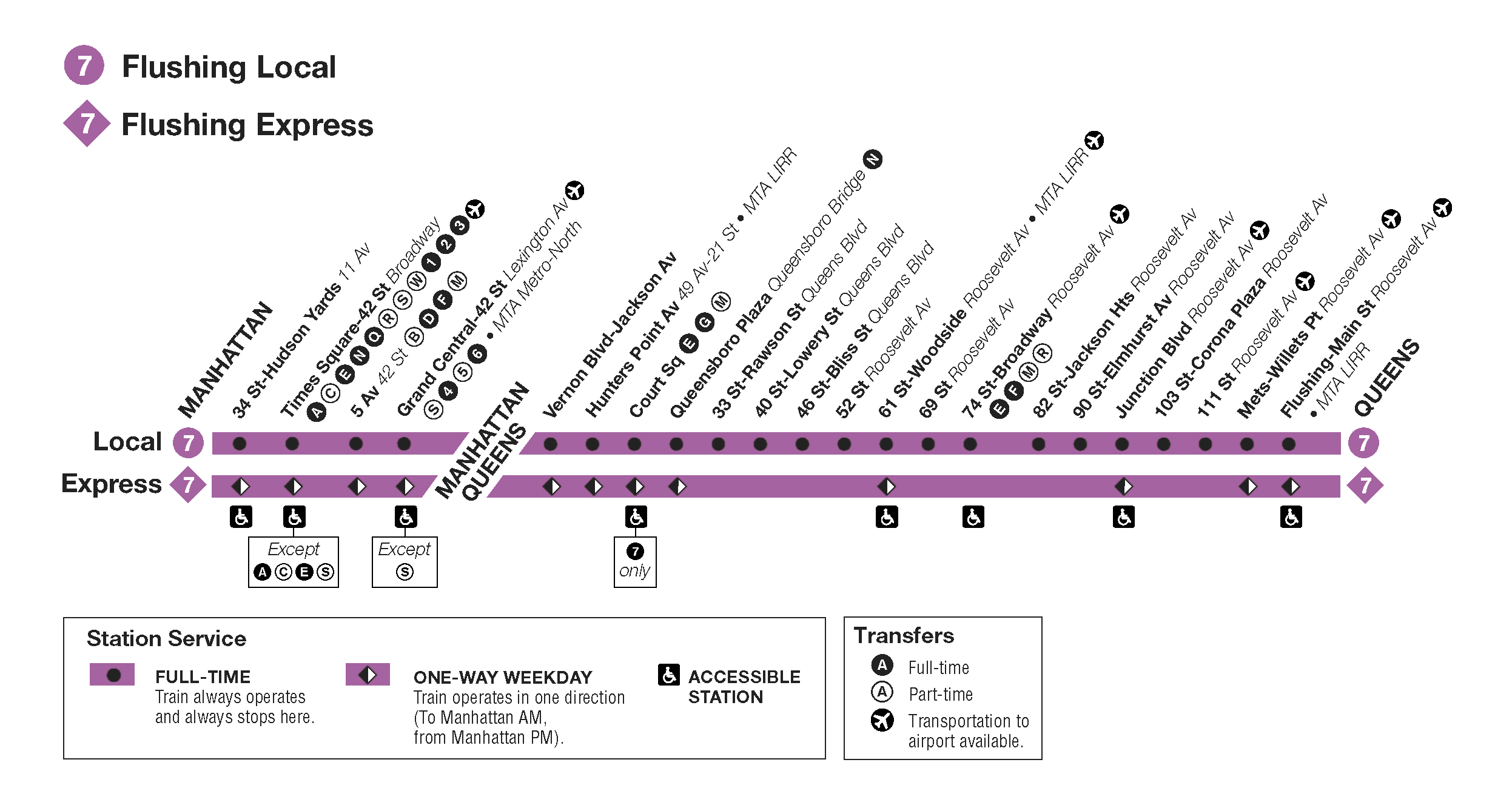

Why Does NYC Subway Have Express Lines?

Why Stop At Two Levels?

From Skip List Data Structure Explained, Sumit’s Diary blog

How TF Does Google Maps Work?

- A (mostly) full-on answer: soon to come! Data structures for spatial data

- A step in that direction: Quadtrees! (Fractal DC)

Algorithmic Complexity: Motivation

The Secretly Exciting World of Matrix Multiplication

- Fun Fact 1: Most of modern Machine Learning is, at the processor level, just a bunch of matrix operations

- Fun Fact 2: The way we’ve all learned how to multiply matrices requires \(O(N^3)\) operations, for two \(N \times N\) matrices \(A\) and \(B\)

- Fun Fact 3: \(\underbrace{x^2 - y^2}_{\mathclap{\times\text{ twice, }\pm\text{ once}}} = \underbrace{(x+y)(x-y)}_{\times\text{once, }\pm\text{ twice}}\)

- Fun Fact 4: These are not very fun facts at all

Why Is Jeff Rambling About Matrix Math From 300 Years Ago?

- The way we all learned it in school (for \(N = 2\)):

\[ AB = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} b_{11} & b_{12} \\ b_{21} & b_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11}b_{11} + a_{12}b_{21} & a_{11}b_{12} + a_{12}b_{22} \\ a_{21}b_{11} + a_{22}b_{21} & a_{21}b_{12} + a_{22}b_{22} \end{bmatrix} \]

- 12 operations: 8 multiplications, 4 additions \(\implies O(N^3) = O(2^3) = O(8)\)

- Are we trapped? Like… what is there to do besides performing these \(N^3\) operations, if we want to multiply two \(N \times N\) matrices? Why are we about to move onto yet another slide about this?

Block-Partitioning Matrices

- Now let’s consider big matrices, whose dimensions are a power of 2 (for ease of illustration): \(A\) and \(B\) are now \(N \times N = 2^n \times 2^n\) matrices

- We can “decompose” the matrix product \(AB\) as:

\[ AB = \begin{bmatrix} A_{11} & A_{12} \\ A_{21} & A_{22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} B_{11} & B_{12} \\ B_{21} & B_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} A_{11}B_{11} + A_{12}B_{21} & A_{11}B_{12} + A_{12}B_{22} \\ A_{21}B_{11} + A_{22}B_{21} & A_{21}B_{12} + A_{22}B_{22} \end{bmatrix} \]

- Which gives us a recurrence relation representing the total number of computations required for this big-matrix multiplication: \(T(N) = \underbrace{8T(N/2)}_{\text{Multiplications}} + \underbrace{\Theta(1)}_{\text{Additions}}\)

- It turns out that (using a method we’ll learn in Week 3), given this recurrence relation and our base case from the previous slide, this divide-and-conquer approach via block-partitioning doesn’t help us: we still get \(T(n) = O(n^3)\)…

- So why is Jeff still torturing us with this example?

Time For Some 🪄MATRIX MAGIC!🪄

- If we define

\[ \begin{align*} m_1 &= (a_{11}+a_{22})(b_{11}+b_{22}) \\ m_2 &= (a_{21}+a_{22})b_{11} \\ m_3 &= a_{11}(b_{12}-b_{22}) \\ m_4 &= a_{22}(b_{21}-b_{11}) \\ m_5 &= (a_{11}+a_{12})b_{22} \\ m_6 &= (a_{21}-a_{11})(b_{11}+b_{12}) \\ m_7 &= (a_{12}-a_{22})(b_{21}+b_{22}) \end{align*} \]

- Then we can combine these seven scalar products to obtain our matrix product:

\[ AB = \begin{bmatrix} m_1 + m_4 - m_5 + m_7 & m_3 + m_5 \\ m_2 + m_4 & m_1 - m_2 + m_3 + m_6 \end{bmatrix} \]

- Total operations: 7 multiplications, 18 additions

Block-Partitioned Matrix Magic

- Using the previous slide as our base case and applying this same method to the block-paritioned big matrices, we get the same result, but where the four entries in \(AB\) here are now matrices rather than scalars:

\[ AB = \begin{bmatrix} M_1 + M_4 - M_5 + M_7 & M_3 + M_5 \\ M_2 + M_4 & M_1 - M_2 + M_3 + M_6 \end{bmatrix} \]

- We now have a different recurrence relation: \(T(N) = \underbrace{7T(N/2)}_{\text{Multiplications}} + \underbrace{\Theta(N^2)}_{\text{Additions}}\)

- And it turns out, somewhat miraculously, that the additional time required for the increased number of additions is significantly less than the time savings we obtain by doing 7 instead of 8 multiplications, since this method now runs in \(T(N) = O(N^{\log_2(7)}) \approx O(N^{2.807}) < O(N^3)\) 🤯

DSAN 5500 Week 2: Software Design Patterns and OOP