Week 8: Privacy Policies, Incomplete Contracts, and Power

DSAN 5450: Data Ethics and Policy

Spring 2026, Georgetown University

Wednesday, March 11, 2026

Privacy Regulations, Privacy Policies, and You

\[ \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmax}{argmax} \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmin}{argmin} \newcommand{\bigexp}[1]{\exp\mkern-4mu\left[ #1 \right]} \newcommand{\bigexpect}[1]{\mathbb{E}\mkern-4mu \left[ #1 \right]} \newcommand{\definedas}{\overset{\small\text{def}}{=}} \newcommand{\definedalign}{\overset{\phantom{\text{defn}}}{=}} \newcommand{\eqeventual}{\overset{\text{eventually}}{=}} \newcommand{\Err}{\text{Err}} \newcommand{\expect}[1]{\mathbb{E}[#1]} \newcommand{\expectsq}[1]{\mathbb{E}^2[#1]} \newcommand{\fw}[1]{\texttt{#1}} \newcommand{\given}{\mid} \newcommand{\green}[1]{\color{green}{#1}} \newcommand{\heads}{\outcome{heads}} \newcommand{\iid}{\overset{\text{\small{iid}}}{\sim}} \newcommand{\lik}{\mathcal{L}} \newcommand{\loglik}{\ell} \DeclareMathOperator*{\maximize}{maximize} \DeclareMathOperator*{\minimize}{minimize} \newcommand{\mle}{\textsf{ML}} \newcommand{\nimplies}{\;\not\!\!\!\!\implies} \newcommand{\orange}[1]{\color{orange}{#1}} \newcommand{\outcome}[1]{\textsf{#1}} \newcommand{\param}[1]{{\color{purple} #1}} \newcommand{\pgsamplespace}{\{\green{1},\green{2},\green{3},\purp{4},\purp{5},\purp{6}\}} \newcommand{\pedge}[2]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{~{#1}~} \rightarrow \; \enclose{circle}{\kern.01em {#2}~\kern.01em}} \newcommand{\pnode}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{\kern.1em {#1} \kern.1em}} \newcommand{\ponode}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{box}[background=lightgray]{{#1}}} \newcommand{\pnodesp}[1]{\require{enclose}\enclose{circle}{~{#1}~}} \newcommand{\purp}[1]{\color{purple}{#1}} \newcommand{\sign}{\text{Sign}} \newcommand{\spacecap}{\; \cap \;} \newcommand{\spacewedge}{\; \wedge \;} \newcommand{\tails}{\outcome{tails}} \newcommand{\Var}[1]{\text{Var}[#1]} \newcommand{\bigVar}[1]{\text{Var}\mkern-4mu \left[ #1 \right]} \]

Regulations: Comparative Perspective

- No single, “universal” data privacy law \(\implies\) compare and contrast various country/state/org attempts to tackle data policy issues

- Important to retain descriptive/normative distinction! They’ll become harder to distinguish as we discuss:

- What are the regulations currently in existence? (Descriptive)

- Do we see a trend? (California Effect vs. Delaware Effect)

- What are their drawbacks? (Normative)

- Fundamental problem of contracts

- Which drawbacks could be addressed “easily” via policy? (requires understanding processes of policy formation)

- Which ones could not? (Prisoner’s Dilemma!)

Present-Day Policy Framework: Notice and Consent

OECD 1980 \(\rightarrow\) EU 1995 \(\rightarrow\) GDPR 2018

OECD Guidelines, 1980

- “The basis for most modern privacy laws” (Sugimoto, Ekbia, and Mattioli 2016)

- Collection Limitation Principle: data may be collected “where appropriate, with the knowledge or consent of the data subject.” (OECD 1980, 14)

- Use Limitation Principle: “Personal data should not be disclosed, made available or otherwise used for purposes other than those specified [at time of collection] except with the consent of the data subject” (OECD 1980, 15)

EU Data Protection Directive, 1995

- Art. 7: Processing allowed when “the data subject has unambiguously given his [sic] consent.”

- Art. 8: Use of sensitive data is restricted, except where “the data subject has given his [sic] explicit consent to the processing of those data.”

- Art. 26: Prohibits export of personal data to non-Euro countries lacking “adequate data protection”, except when “the data subject has given his [sic] consent unambiguously to the proposed transfer” (European Union 1995)

- Superceded by GDPR in 2018

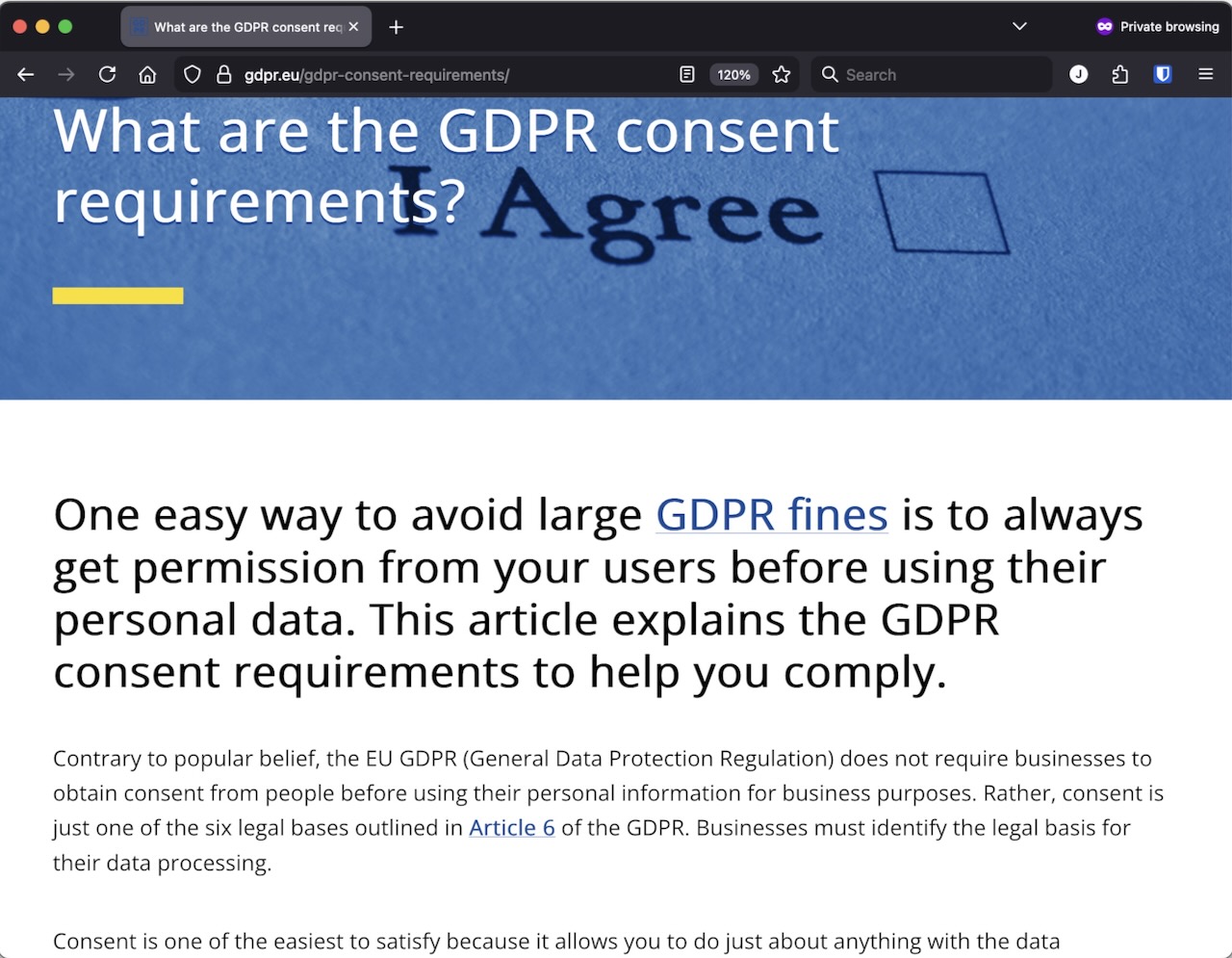

EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), 2018

Effects of GDPR…

From Demirer et al. (2024)

- Need to be careful about interpretation!

- Could be due to less tracking, could also be due to monopolization

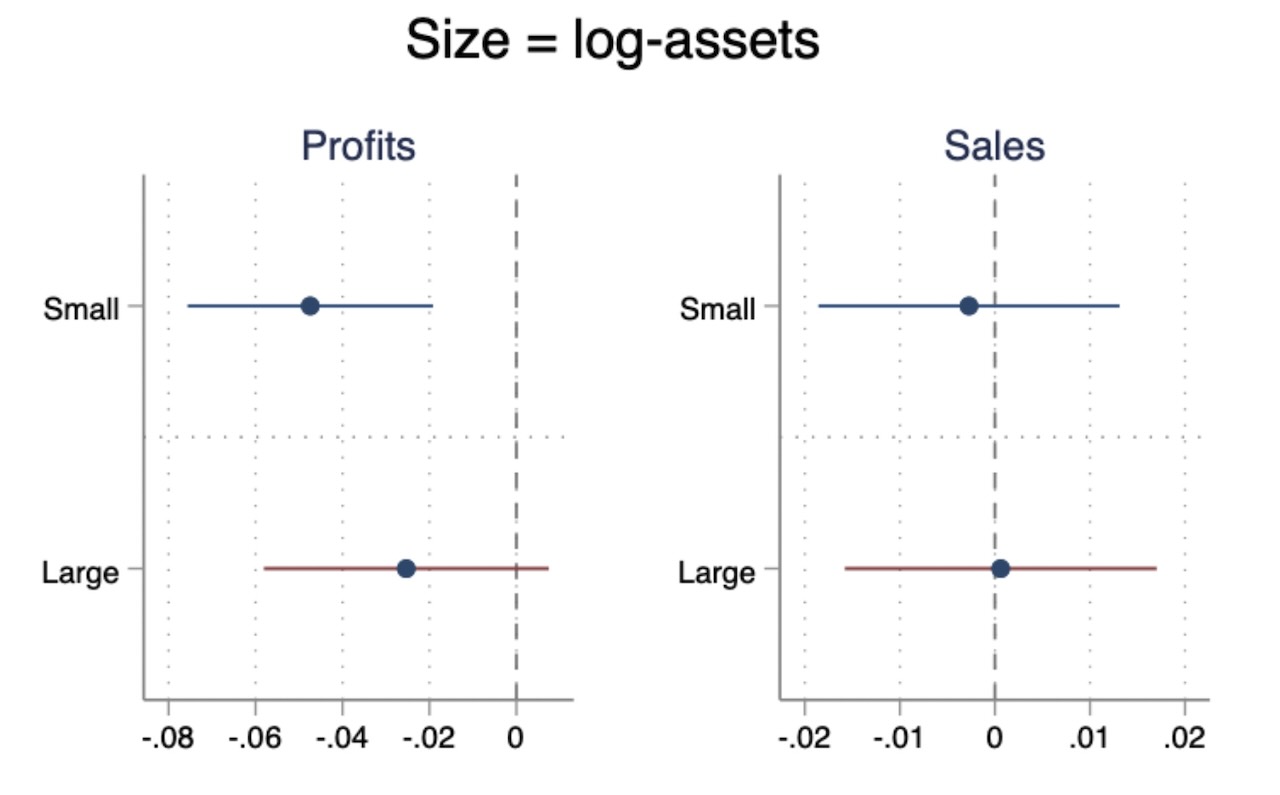

Effects of GDPR: Effect on Who?

Consumers: Reduced tracking

The GDPR lowered the average number of trackers by about four trackers per publisher

Firms: Harsher impact on small firms

Despite data minimization successes, GDPR had the unintended consequence of increasing relative concentration

Distributional Effects

From Demirer et al. (2024)

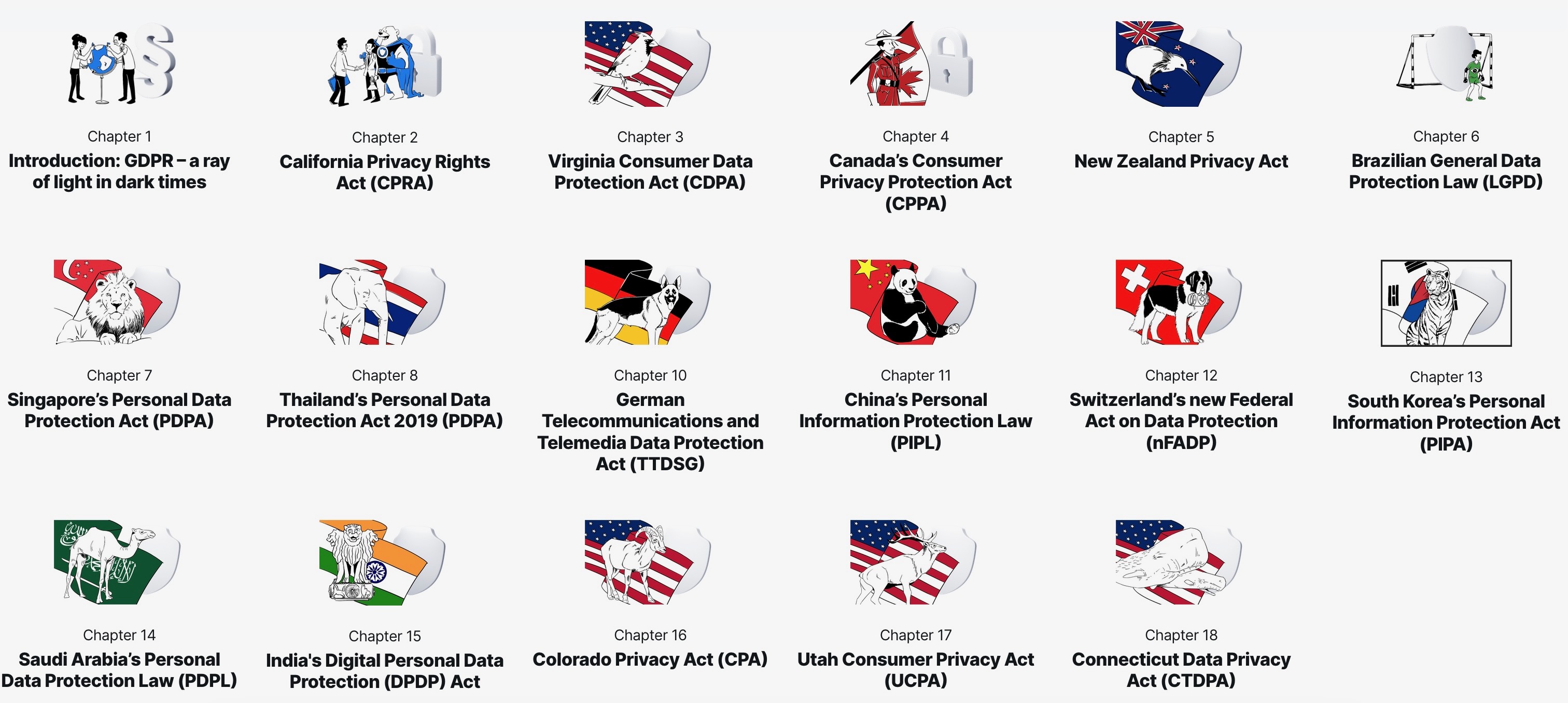

Going Beyond Just GDPR…

From Piwik.pro, “17 Privacy Laws Around the Globe”

Easy Mode: Policy Diffusion

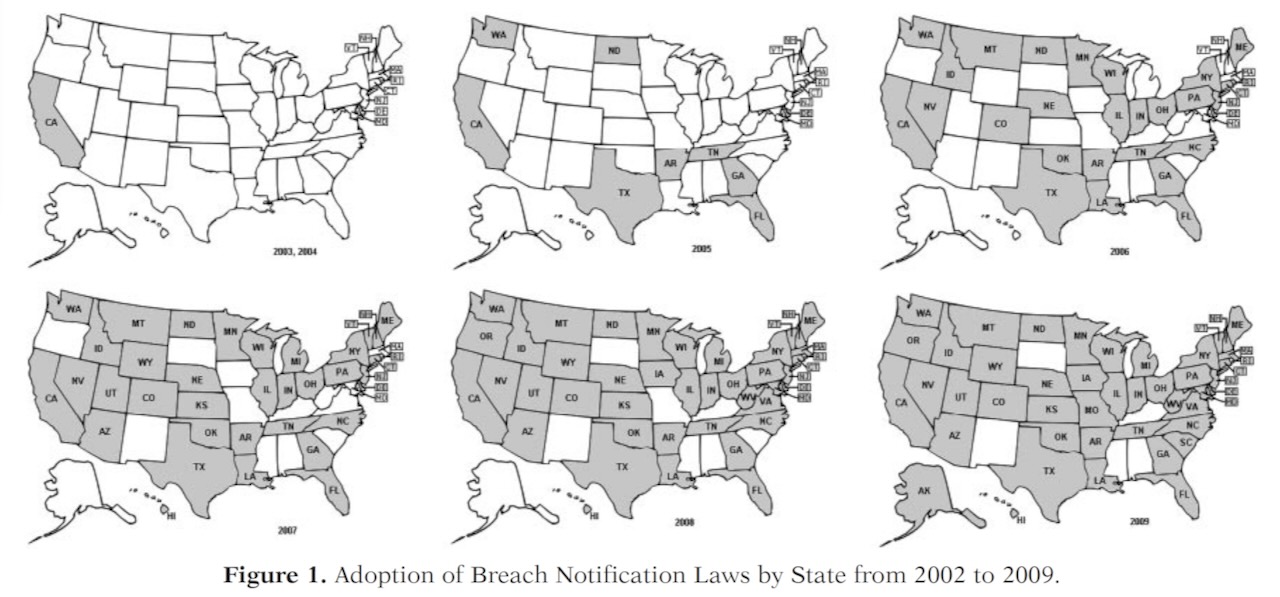

From Romanosky, Telang, and Acquisti (2011)

(Policy Diffusion Curve!)

Hard Mode: Impact of Policy Diffusion

Result (Note the explicitly-identified independent \(\rightarrow\) dependent vars!):

Dep Var: log(idtheft) |

Basic | Basic + Controls |

|---|---|---|

hasLaw |

–0.050* (0.026) |

–0.061*** (0.023) |

| Income per capita | 0.000 (0.000) |

|

| Unemployment rate | 0.003 (0.010) |

|

| Log(population) | –0.268 (0.343) |

|

| State and time fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Constant | 6.852*** (0.014) |

11.248** (5.317) |

| R-squared | 0.848 | 0.850 |

| ***: \(p < 0.01\) | **: \(p < 0.05\) | *: \(p < 0.1\) |

(Normative) Issues with Notice and Consent

The Crux of the Normative Issues

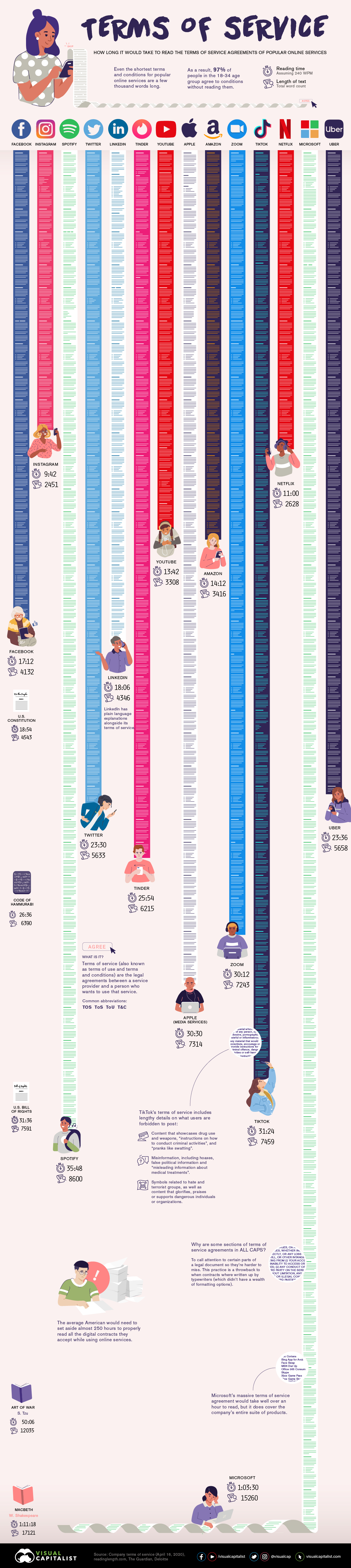

Does Reading = Understanding?

- Does reading \(\implies\) understanding implications / contingencies / ambiguities?

- NLP could (and should!) be helpful (“making privacy policies machine readable […] would help users match privacy preferences against policies offered by web services”), but mostly just reveals how bad the problem is:

Figure 15 from Wagner (2023). “Obfuscatory words” are words like acceptable, significant, mainly, or predominantly, interpretated at the discretion of companies rather than users (see next slide!)

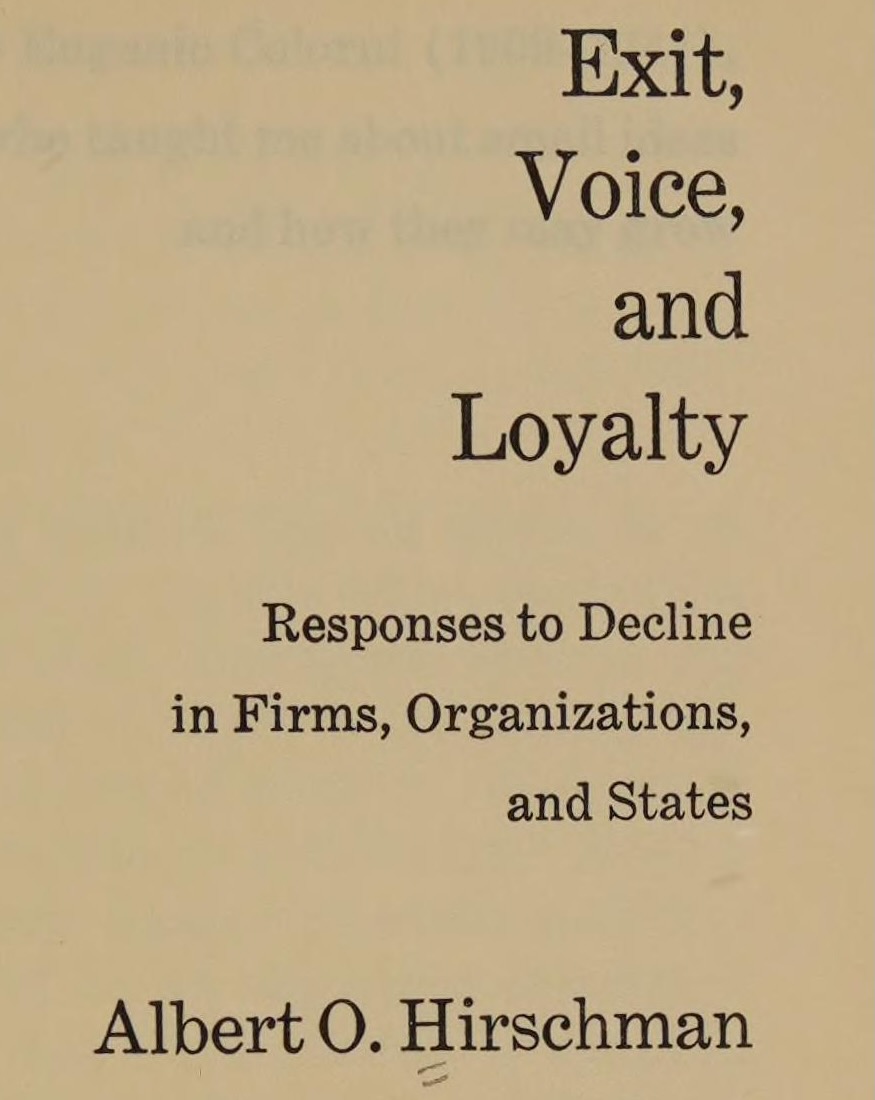

The Intuitive Problem of Contracts

- Hard to read, harder to understand, possibly rly bad stuff in them, won’t know until you read + understand

- Solution (in theory… in modern liberal market-based democracies): Collective action!

- Option 1 (Exit): Find better platform, use it instead \(\Rightarrow\) company dies (competitive market)

- Option 2 (Voice): Raise a fuss, hoot and holler, make a big stink about it, etc.

- \(\Rightarrow\) (2a) Company will change/remove it to avoid embarrassment and/or prevent Option 1 becoming an option

- \(\Rightarrow\) (2b) Government intervention (hypothetical functional government)

The Fundamental Problem of Contracts

- Just as we can’t observe two simultaneous worlds \(W_{X = 0}\) and \(W_{X = 1}\) which differ only in the value of \(X\),

- We can’t foresee all possible contingencies that need to be included in a contract

- (We can try, though! Hence use of obfuscatory words to minimize liability)

- So, when a situation arises which is not covered by a clause in the contract, what happens? What principle determines whose interpretation wins out?

- (Hint: It is actually literally my legal middle name…)

…POWER!

- Examples from employment contracts (tooting own horn):

- In a private, cooperatively-owned, democratic firm, outcome determined by conversation, majority vote, unanimity, etc.

- These technically exist in the US! Employing 2,380 workers, \(\frac{2380}{127509000} \approx 0.0019\%\) of US workforce

- Otherwise, in a non-unionized private firm (94% of total), the outcome is determined by organizational hierarchy

- This is the case for \(\frac{125000000}{127509000} \approx 98.03\%\) of US workforce

Descriptive and Normative Implications

- Who has power w.r.t. incompleteness of contracts?

- Who ought to have power w.r.t. incompleteness of contracts?

- Residual rights of control…

Hart’s Nobel Prize Speech

Complete contracts are contracts where everything that can ever happen is written into the contract. Actual contracts aren’t like this, as lawyers know. They’re poorly worded, ambiguous, leave out important things. They’re incomplete.

A critical question that arises with an incomplete contract is, who has the right to decide about the missing things? We called this right the residual control or decision right. The question is, who has it?

Further thought led us to the idea that this is what ownership is. The owner of an asset has the right to decide how the asset is used where the use is not contractually specified (Hart 2017)

Understanding Rights \(\leftrightarrow\) Fighting for Rights

- “Hohfeldian” framework (Hohfeld 1913)

- A right \(r_i\) granted to person \(i\) \(\implies\) A duty/obligation imposed on everyone in the world besides \(i\) (to respect \(r_i\))

- A duty or obligation \(d_i\) imposed on a person \(i\) \(\implies\) A right granted to everyone in the world besides \(i\) (to… be a potential beneficiary of \(d_i\))

- \(\implies\) rough measures of relative power in a contract:

\[ \frac{\text{rights}_i}{\text{rights}_j} = \frac{\text{obligations}_j}{\text{rights}_j} = \frac{\text{rights}_i}{\text{obligations}_j} = \frac{\text{obligations}_j}{\text{obligations}_i} \]

The Adversarial-Sisyphusian Problem of Contracts

- Recall Intuitive Problem of Causal Inference: Correlation \(\nimplies\) Causation, but can do a bunch of work to overcome

- Adversarial-Sisyphusian Problem is one level worse 😱

- IPCI: You vs. discovered correlation (inanimate)

- ASPC: You vs. companies investing resources 💰 into making the problem harder and harder for you

- tldr: The moment you (\(N=1\), $) finally find and “fix” bad thing, company (\(N \gg 1\), $$$) adds more ambiguity to re-enable / sends your data to "new", "different" 3rd-party processor 🥸

References

DSAN 5450 Week 8: Privacy Policies, Incomplete Contracts, and Power