Our first algorithm, insertion sort, solves the sorting problem introduced in Chapter 1:

Input: A sequence of numbers

Output: A permutation (reordering) of the input sequence such that .

The numbers to be sorted are also known as the keys. Although the problem is conceptually about sorting a sequence, the input comes in the form of an array with elements. When we want to sort numbers, it’s often because they are the keys associated with other data, which we call satellite data. Together, a key and satellite data form a record. For example, consider a spreadsheet containing student records with many associated pieces of data such as age, grade-point average, and number of courses taken. Any one of these quantities could be a key, but when the spreadsheet sorts, it moves the associated record (the satellite data) with the key. When describing a sorting algorithm, we focus on the keys, but it is important to remember that there usually is associated satellite data.

In this book, we’ll typically describe algorithms as procedures written in a pseudocode that is similar in many respects to C, C++, Java, Python,[1] or JavaScript. (Apologies if we’ve omitted your favorite programming language. We can’t list them all.) If you have been introduced to any of these languages, you should have little trouble understanding algorithms “coded” in pseudocode. What separates pseudocode from real code is that in pseudocode, we employ whatever expressive method is most clear and concise to specify a given algorithm. Sometimes the clearest method is English, so do not be surprised if you come across an English phrase or sentence embedded within a section that looks more like real code. Another difference between pseudocode and real code is that pseudocode often ignores aspects of software engineering -- such as data abstraction, modularity, and error handling -- in order to convey the essence of the algorithm more concisely.

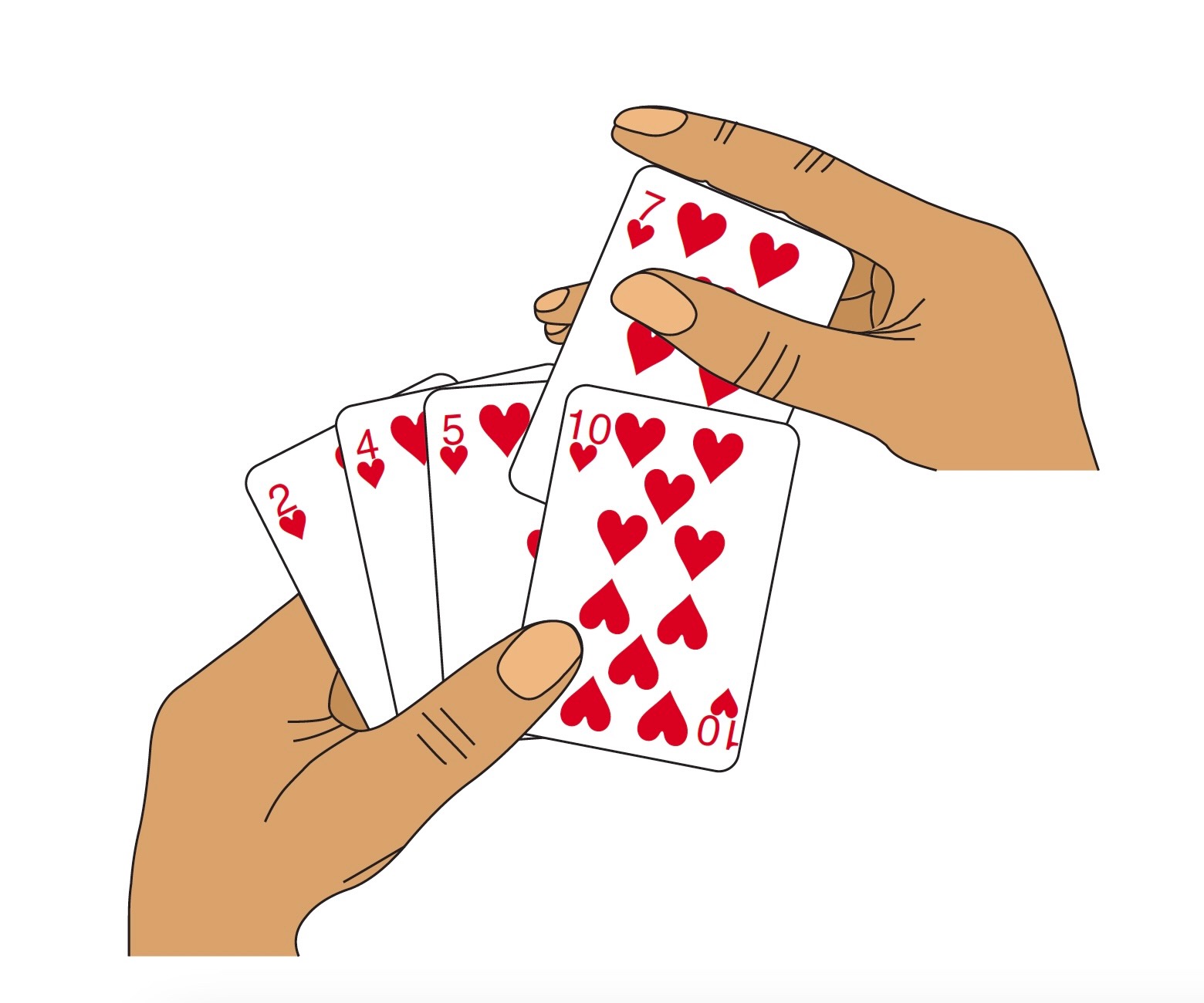

We start with insertion sort, which is an efficient algorithm for sorting a small number of elements. Insertion sort works the way you might sort a hand of playing cards. Start with an empty left hand and the cards in a pile on the table. Pick up the first card in the pile and hold it with your left hand. Then, with your right hand, remove one card at a time from the pile, and insert it into the correct position in your left hand. As Figure 1 illustrates, you find the correct position for a card by comparing it with each of the cards already in your left hand, starting at the right and moving left. As soon as you see a card in your left hand whose value is less than or equal to the card you’re holding in your right hand, insert the card that you’re holding in your right hand just to the right of this card in your left hand. If all the cards in your left hand have values greater than the card in your right hand, then place this card as the leftmost card in your left hand. At all times, the cards held in your left hand are sorted, and these cards were originally the top cards of the pile on the table.

The pseudocode for insertion sort is given as the procedure Insertion-Sort on the facing page. It takes two parameters: an array containing the values to be sorted and the number of values of sort. The values occupy positions through of the array, which we denote by . When the Insertion-Sort procedure is finished, array contains the original values, but in sorted order.

Figure 1:Sorting a hand of cards using insertion sort.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9INSERTION-SORT(A, n) for i = 2 to n key = A[i] # Insert A[i] into the sorted subarray A[1:i-1] j = i - 1 while j > 0 and A[j] > key A[j+1] = A[j] j = j - 1 A[j + 1] = key

Loop invariants and the correctness of insertion sort¶

Figure 2:The operation of Insertion-Sort, where initially contains the sequence and . Array indices appear above the rectangles, and values stored in the array positions appear within the rectangles. (a)–(e) The iterations of the for loop of lines 1-8. In each iteration, the blue rectangle holds the key taken from , which is compared with the values in tan rectangles to its left in the test of line 5. Orange arrows show array values moved one position to the right in line 6, and blue arrows indicate where the key moves to in line 8. (f) The final sorted array.

Figure 2 shows how this algorithm works for an array that starts out with the sequence . The index indicates the “current card” being inserted into the hand. At the beginning of each iteration of the for loop, which is indexed by , the subarray (a contiguous portion of the array) consisting of elements (that is, through ) constitutes the currently sorted hand, and the remaining subarray (elements through ) corresponds to the pile of cards still on the table. In fact, elements are the elements originally in positions 1 through , but now in sorted order. We state these properties of formally as a loop invariant:

Loop invariants help us understand why an algorithm is correct. When you’re using a loop invariant, you need to show three things:

Initialization: It is true prior to the first iteration of the loop.

Maintenance: If it is true before an iteration of the loop, it remains true before the next iteration.

Termination: The loop terminates, and when it terminates, the invariant -- usually along with the reason that the loop terminated -- gives us a useful property that helps show that the algorithm is correct.

When the first two properties hold, the loop invariant is true prior to every iteration of the loop. (Of course, you are free to use established facts other than the loop invariant itself to prove that the loop invariant remains true before each iteration.) A loop-invariant proof is a form of mathematical induction, where to prove that a property holds, you prove a base case and an inductive step. Here, showing that the invariant holds before the first iteration corresponds to the base case, and showing that the invariant holds from iteration to iteration corresponds to the inductive step.

The third property is perhaps the most important one, since you are using the loop invariant to show correctness. Typically, you use the loop invariant along with the condition that caused the loop to terminate. Mathematical induction typically applies the inductive step infinitely, but in a loop invariant the “induction” stops when the loop terminates.

Let’s see how these properties hold for insertion sort.

Initialization: We start by showing that the loop invariant holds before the first loop iteration, when .[2] The subarray consists of just the single element , which is in fact the original element in . Moreover, this subarray is sorted (after all, how could a subarray with just one value not be sorted?), which shows that the loop invariant holds prior to the first iteration of the loop.

Maintenance: Next, we tackle the second property: showing that each iteration maintains the loop invariant. Informally, the body of the

forloop works by moving the values in , , , and so on by one position to the right until it finds the proper position for (lines 4-7), at which point it inserts the value of (line 8). The subarray then consists of the elements originally in , but in sorted order. Incrementing (increasing its value by 1) for the next iteration of the for loop then preserves the loop invariant. A more formal treatment of the second property would require us to state and show a loop invariant for thewhileloop of lines 5-7. Let’s not get bogged down in such formalism just yet. Instead, we’ll rely on our informal analysis to show that the second property holds for the outer loop.Termination: Finally, we examine loop termination. The loop variable starts at 2 and increases by 1 in each iteration. Once ’s value exceeds in line 1, the loop terminates. That is, the loop terminates once equals . Substituting for in the wording of the loop invariant yields that the subarray consists of the elements originally in , but in sorted order. Hence, the algorithm is correct.

This method of loop invariants is used to show correctness in various places throughout this book.

Pseudocode conventions¶

We use the following conventions in our pseudocode.

Indentation indicates block structure. For example, the body of the

forloop that begins on line 1 consists of lines 2-8, and the body of thewhileloop that begins on line 5 contains lines 6-7 but not line 8. Our indentation style applies toif-elsestatements[3] as well. Using indentation instead of textual indicators of block structure, such asbeginandendstatements or curly braces, reduces clutter while preserving, or even enhancing, clarity.[4]The looping constructs

while,for, andrepeat-untiland theif-elseconditional construct have interpretations similar to those in C, C++, Java, Python, and JavaScript.[5] In this book, the loop counter retains its value after the loop is exited, unlike some situations that arise in C++ and Java. Thus, immediately after aforloop, the loop counter’s value is the value that first exceeded theforloop bound.[6] We used this property in our correctness argument for insertion sort. Theforloop header in line 1 isforto, and so when this loop terminates, equals . We use the keywordtowhen aforloop increments its loop counter in each iteration, and we use the keyworddowntowhen aforloop decrements its loop counter (reduces its value by 1 in each iteration). When the loop counter changes by an amount greater than 1, the amount of change follows the optional keywordby.The symbol “

//” indicates that the remainder of the line is a comment.Variables (such as

i,j, andkey) are local to the given procedure. We won’t use global variables without explicit indication.We access array elements by specifying the array name followed by the index in square brackets. For example, indicates the th element of the array .

Although many programming languages enforce 0-origin indexing for arrays (0 is the smallest valid index), we choose whichever indexing scheme is clearest for human readers to understand. Because people usually start counting at 1, not 0, most -- but not all -- of the arrays in this book use 1-origin indexing. To be clear about whether a particular algorithm assumes 0-origin or 1-origin indexing, we’ll specify the bounds of the arrays explicitly. If you are implementing an algorithm that we specify using 1-origin indexing, but you’re writing in a programming language that enforces 0-origin indexing (such as C, C++, Java, Python, or JavaScript), then give yourself credit for being able to adjust. You can either always subtract 1 from each index or allocate each array with one extra position and just ignore position 0.

The notation “” denotes a subarray. Thus, indicates the subarray of consisting of the elements .[7] We also use this notation to indicate the bounds of an array, as we did earlier when discussing the array .

We typically organize compound data into objects, which are composed of attributes. We access a particular attribute using the syntax found in many object-oriented programming languages: the object name, followed by a dot, followed by the attribute name. For example, if an object has attribute , we denote this attribute by . We treat a variable representing an array or object as a pointer (known as a reference in some programming languages) to the data representing the array or object. For all attributes of an object , setting causes to equal . Moreover, if we now set , then afterward not only does equal 3, but equals 3 as well. In other words, and point to the same object after the assignment . This way of treating arrays and objects is consistent with most contemporary programming languages.

Our attribute notation can “cascade.” For example, suppose that the attribute is itself a pointer to some type of object that has an attribute . Then the notation is implicitly parenthesized as . In other words, if we had assigned , then is the same as .

Sometimes a pointer refers to no object at all. In this case, we give it the special value nil.

We pass parameters to a procedure by value: the called procedure receives its own copy of the parameters, and if it assigns a value to a parameter, the change is not seen by the calling procedure. When objects are passed, the pointer to the data representing the object is copied, but the object’s attributes are not. For example, if is a parameter of a called procedure, the assignment within the called procedure is not visible to the calling procedure. The assignment , however, is visible if the calling procedure has a pointer to the same object as . Similarly, arrays are passed by pointer, so that a pointer to the array is passed, rather than the entire array, and changes to individual array elements are visible to the calling procedure. Again, most contemporary programming languages work this way.

A

returnstatement immediately transfers control back to the point of call in the calling procedure. Mostreturnstatements also take a value to pass back to the caller. Our pseudocode differs from many programming languages in that we allow multiple values to be returned in a single return statement without having to create objects to package them together.[8]The boolean operators “and” and “or” are short circuiting. That is, evaluate the expression “ and ” by first evaluating . If evaluates to

False, then the entire expression cannot evaluate toTrue, and therefore is not evaluated. If, on the other hand, evaluates toTrue, must be evaluated to determine the value of the entire expression. Similarly, in the expression “ or ” the expression is evaluated only if evaluates toFalse. Short-circuiting operators allow us to write boolean expressions such as “nil and ” without worrying about what happens upon evaluating when is nil.The keyword

errorindicates that an error occurred because conditions were wrong for the procedure to have been called, and the procedure immediately terminates. The calling procedure is responsible for handling the error, and so we do not specify what action to take.

Exercises¶

2.1-1¶

Using Figure 2 as a model, illustrate the operation of Insertion-Sort on an array initially containing the sequence .

2.1-2¶

Consider the procedure Sum-Array below. It computes the sum of the numbers in array . State a loop invariant for this procedure, and use its initialization, maintenance, and termination properties to show that the Sum-Array procedure returns the sum of the numbers in .

1 2 3 4 5SUM-ARRAY(A, n) sum = 0 for i = 1 to n sum = sum + A[i] return sum

2.1-3¶

Rewrite the Insertion-Sort procedure to sort into monotonically decreasing instead of monotonically increasing order.

2.1-4¶

Consider the searching problem:

Input: A sequence of numbers stored in array and a value .

Output: An index such that equals or the special value nil if does not appear in .

Write pseudocode for linear search, which scans through the array from beginning to end, looking for . Using a loop invariant, prove that your algorithm is correct. Make sure that your loop invariant fulfills the three necessary properties.

2.1-5¶

Consider the problem of adding two n-bit binary integers and , stored in two -element arrays and , where each element is either 0 or 1, , and .

The sum of the two integers should be stored in binary form in an -element array , where .

Write a procedure Add-Binary-Integers that takes as input arrays and , along with the length , and returns array holding the sum.

If you’re familiar with only Python, you can think of arrays as similar to Python lists.

When the loop is a

forloop, the loop-invariant check just prior to the first iteration occurs immediately after the initial assignment to the loop-counter variable and just before the first test in the loop header. In the case of Insertion-Sort, this time is after assigning 2 to the variable but before the first test of whether .In an

if-elsestatement, we indentelseat the same level as its matchingif. The first executable line of anelseclause appears on the same line as the keywordelse. For multiway tests, we useelseiffor tests after the first one. When it is the first line in anelseclause, anifstatement appears on the line followingelseso that you do not misconstrue it aselseif.Each pseudocode procedure in this book appears on one page so that you do not need to discern levels of indentation in pseudocode that is split across pages.

Most block-structured languages have equivalent constructs, though the exact syntax may differ. Python lacks

repeat-untilloops, and itsforloops operate differently from theforloops in this book. Think of the pseudocode line “forto” as equivalent to “for i in range(1, n+1)” in Python.In Python, the loop counter retains its value after the loop is exited, but the value it retains is the value it had during the final iteration of the

forloop, rather than the value that exceeded the loop bound. That is because a Pythonforloop iterates through a list, which may contain nonnumeric values.If you’re used to programming in Python, bear in mind that in this book, the subarray includes the element . In Python, the last element of is . Python allows negative indices, which count from the back end of the list. This book does not use negative array indices.

Python’s tuple notation allows

returnstatements to return multiple values without creating objects from a programmer-deûned class.