You Can’t ‘Agree to Disagree’ on a Moving Train, Unfortunately

There’s a book I read and use every year for the very beginning of my data ethics course, R. M. Hare’s The Language of Morals (Hare 1952). The reason I love it is, I’m guessing, similar to why Karl Marx loved David Ricardo: Marx saw how Ricardo, despite being an “apologist” for capitalism, analyzed capitalism so sharply that he inadvertently revealed its flaws.

Similarly, though Hare’s work is broadly placed within the general canon of liberal ethical thought, he writes things like this which seem to inadvertently undermine the liberal notion of “agreeing to disagree”:

Suppose that a Communist and I are arguing about whether I ought to do a certain act \(A\); and suppose that on his principles I ought not to do it, whereas on mine I ought to do it.

[A liberal might then propose that], in order to avoid such disputes, it would be better for us to substitute two unambiguous terms for the one ambiguous one; for example, the Communist should use the term \(\textsf{ought}_1\) for the concept governed by his rules of verification, and I should use \(\textsf{ought}_2\) for my concept.

But the point is that there is a dispute, and not merely a verbal misunderstanding, between the Communist and me; we are differing about what I ought to do (not what I ought to say) and, if he convinces me, my conduct will be substantially different from what it would be if I remained unconvinced.

Trust me, for the sake of sleeping at night, I wish more than anything that “neutrality” – agreeing to disagree – was a tenable position to take on issues where our actions matter (for example, off the top of my head… the issue of whether to act to try and make Georgetown divest its funds from Israeli companies). But alas, what happens in the future is by definition a function of the choices we all make in the present. And, if there is an ongoing ethnic cleansing project happening in that present, then, unfortunately, part of the impact we might have on ending this project comes in the form of persuasion.

Turning from ethics in the abstract to concrete (consequentialist) social change1, studying history gives us a “way out” (for lack of a better term). We can try our best to study, empirically, the most horrific historical instances of oppression: slavery, apartheid, ethnic cleansing, genocide, and so on. Were they eventually ended? If so, how was this achieved?

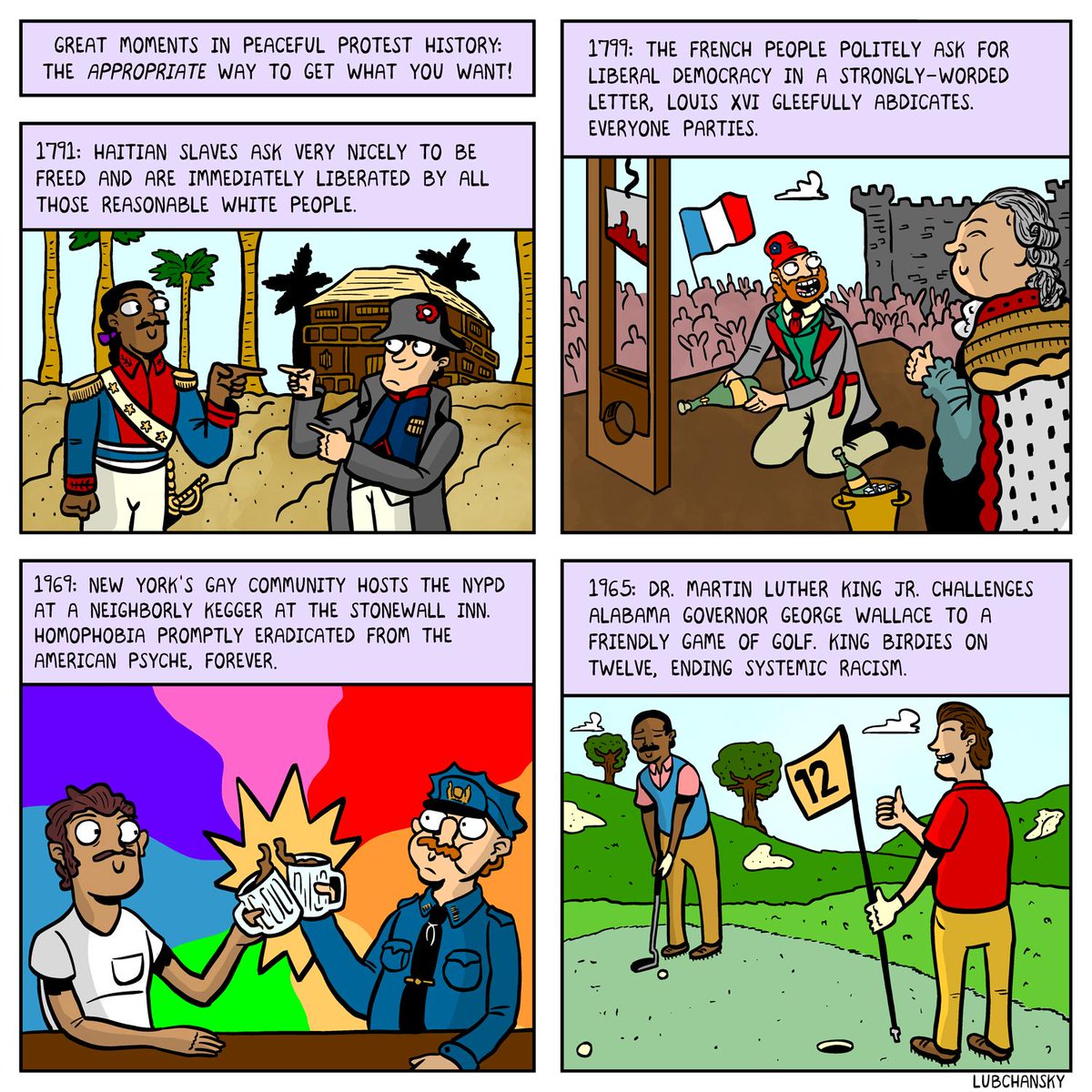

And if we ask that question honestly, if we do what I try my best to do and “deep dive” the historical trajectory of each instance… then (again, unfortunately), the historical record in my reading unambiguously points to how the persuasion that Hare’s book is about is not what causes oppression to end. What does actually bring about the end of oppression? This comic illustrates the answer better than my words can:

References

Footnotes

Or, to put it another way… turning from what keeps me up at night to what eventually allows me to sleep↩︎